http://etd.lib.umt.edu/theses/available/etd-12152006-100028/unrestricted/Thesis.pdf

In 2004, Douglas Wallace of the University of California at Irvine and his colleagues reported signs of natural selection in human mitochondria - the fuel-generating factories of the cell. Mitochondria convert the glucose in food into a compound called adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which the cell can then use as fuel as it crawls around, produces hormones or performs some other task. The production of ATP releases heat as a byproduct, which can help keep our bodies warm.

Studying over 1,000 people, Wallace and his colleagues discovered that people in Europe and northeastern Siberia have inherited unusual mutations in their mitochondrial DNA that can't be found in the genes of Africans. These mutations appear to make European and Siberian mitochondria produce more heat. Wallace and his colleagues suggest that these mutations brought benefits to humans as they moved into cold climates.

https://profgrant.com/2016/08/01/the-thrifty-gene-found-in-samoa-and-what-it-means/

The Island of Korsae, a speck of reef-fringed rainforest in the

middle of the Pacific, is one of the most gorgeous and unspoiled places

on earth. Tourism has not yet desecrated the island with four-story

cabana-style resorts because Korsae is so utterly remote from just about

anywhere else...Such an idyllic and out-of-the-way island, with fresh

reef fish, rainforest fruit and plenty of sunshine, should be the

perfect place to live a healthy and well-nourished life. Unfortunately,

at last estimate, nine out of ten adult residents Korsae were officially

overweight and three out of five were obese.

Those are

staggering numbers, but Korsae is by no means the only place where such

a high proportion of people are overweight. In fact, the federate

states of Micronesia, of which Korsae is the smallest state, ranks only

sixth among nations by the proportion of people who are obese.

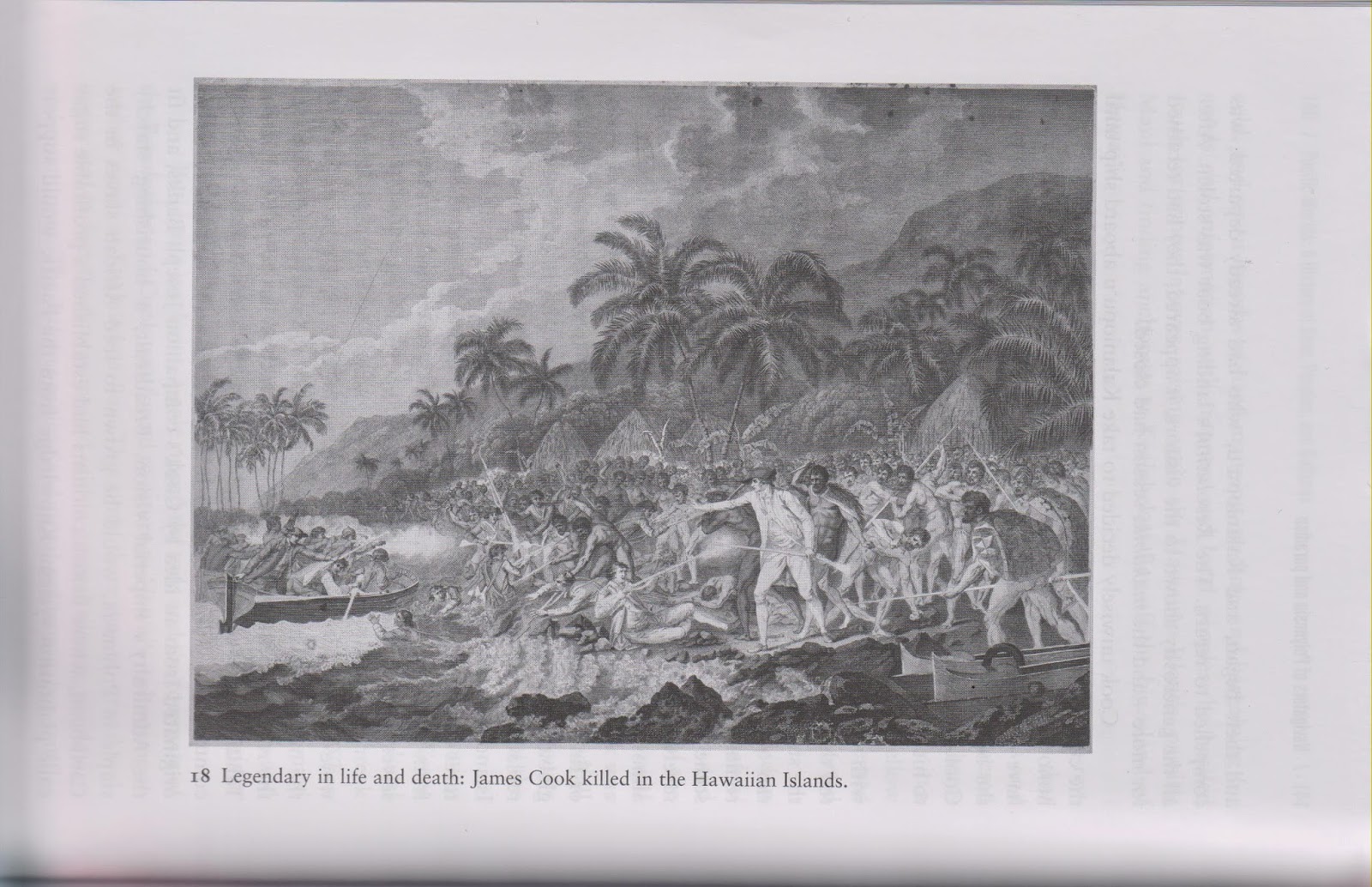

Strikingly, the top seven are all Pacific islands. Obesity was not

always this common in the Pacific;early European explorers found the

inhabitants physically impressive, lean and powerful in build. But

obesity erupted in the Pacific, as in many other parts of the world, in

the late twentieth century. Luckily we know a lot about the social and

economic changes that occurred around the same time, which are probably

part of the cause.

...

In order to

illustrate the complex and subtle interplay of genes and environment in

obesity, we need to revisit the Pacific Islanders. Their ancestors

gradually colonized the Pacific over the last 8000 years, from which

time until very recently they ate a diet rich in fresh reef fish and

tuna. This is about as healthy a dietary foundation as you can get: high

in protein and the healthiest fats. They also ate vegetables and fruit

high in fiber and complex carbohydrates such as breadfruit, taro, yams,

cassava and bananas; and coconuts, which are rich in the healthiest

fats. Agriculture on Pacific islands was confined largely to these

fruits and root crops. There was probably seldom great overabundance of

food, and probably periodic hunger, including the very real chance of

going days without food if a fishing trip fell foul of weather or

currents. As a result, Pacific islanders are probably among the peoples

whose ancestors never experienced the very high carbohydrate diets that

characterize transitions to agriculture. Pacific islanders may also have

adapted to the presence of abundant fresh fish, evolving a higher

protein intake target than people in many other parts of the world.

Recent

modernization in the Pacific reduced both physical activity and

reliance on traditional foods. At the same time imports of salted and

processed foods full of saturated fats and cheap carbohydrates rose.

Since the 1950s, life in Micronesia has changed substantially with the

rise of a cash economy fueled first by US subsidies and then by the sale

of tuna fishing rights to Japan. As a result, the local foods have been

steadily supplanted by rice, wheat flour, sugar, tinned fish, fatty

tinned meats, and turkey tails.

The tale of the turkey

tail is typical of the tragedy. Turkey tails are gristly, fatty skin

flaps cut from American Thanksgiving and Christmas turkeys and either

discarded, used for pet food or exported frozen to poor places like

Micronesia where they are sold to the poorest citizens. The U.S.

department of Agriculture's supplementary feeding program, which

provides school lunches compromising tinned fish, tinned meats and rice,

has also been blamed for increasing food dependency and replacing the

production and consumption of healthy local foods with less healthy

imported alternatives.

I don't have much of a palate

for conspiracy theories, and goodness knows there are enough of them

surrounding the modern diet. I think that obesity on Korsae and

elsewhere in the Pacific is far more interesting than a conspiracy

theory could ever be. It seems likely that a very unfortunate confluence

of interlinked political and commercial interests as well as global

economic changes and the challenges faced by most developing nations

have had the largely unintended effect of changing diets in places like

Korsae, Nauru, the Cook islands and Samoa. The shift from a very healthy

locally sourced diet rich in fish protein, healthy fats and complex

carbohydrates to a diet full of low-quality tinned protein, cereal grain

staples and sugar has been hastened by poverty, the transition to a

cash economy and the growing influence of foreign developed nations.

Sex, Genes, and Rock 'N' Roll: How Evolution Has Shaped The Modern World. Brooks, p.38-39 54-56

As I described, people at higher latitudes are on average heavier than those at lower latitudes. The

other part of the world where we find that the native peoples, the

original inhabitants, are relatively large is on the Pacific islands, at

the opposite extreme of the geographic world from the poles. Some of

the heaviest people in the world are Samoans.

Rather

than having Artic peoples' solid body build, though, the large Pacific

islanders are simply fat. Recent figures from the World Health

Organization indicate that nearly three quarters of Samoans are obese.

In other words, they have abody mass index (often abbreviated as BMI) of

more than thirty, the threshold for classification as obese. For other

Pacific islands, the proportions of the population with such high body

mass indices range from forty to seventy-five percent of the population.

By comparison, the proportions for two countries often considered

overweight, the UK and USA, are just twenty-five percent and thirty-five

percent respectively.

https://www.maxwell.syr.edu/uploadedFiles/moynihan/dst/curtis5.pdf?n=3228

POLYNESIANS ARE BORN FAT AND WITH THE GENES TO EASILY BECOME FATTER AND THEY DO SO BY CONSUMING A STEADY INTAKE OF FOOD LIKE THAT PICTURED IN THE LINK ABOVE. (WE EAT THE FOOD THAT OUR PEER GROUP EATS AND OUR PEER GROUP EATS THE FOOD THAT THE MAINSTREAM CULTURE INFLUENCES THE PEER GROUP TO EAT. AND WHAT DOES MAINSTREAM AMERICAN CULTURE INFLUENCE PEOPLE TO EAT? SHIT! EAT SHIT AND DIE BITCH!)

Body mass index is

calculated as mass in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. It

so happens that those two easily measured values, weight and height

correspond more or less to the percentage of fat in a normal human body

when combined in the equation that I have just described. Of course, the

values vary depending on sex, age, and the sort of exercise we taken,

given that bone and muscle also affect our total weight. But as a near

approximation, the equation adequately indicates body fat.

Why

are Pacific Islanders so prone to fat? Look at a globe and think about

the original journeys to those islands. The Pacific Ocean covers nearly

half the globe. The initial trips to the Pacific Islands covered

thousands of kilometers in open boats. The travelers would have been

soaked much of the time, and probably half starved by the time they got

to an island, let alone by the time they produced their first crop. It

is easy to imagine that the people who survived best were those with the

most efficient metabolism, a metabolism that was best at converting food

to fat.

Once

established on an island, if harvest failed, survivors could not easily

move elsewhere. They would have to sit out the bad period. Again, those

individuals with he most efficient metabolism would have been the ones

most likely to survive. In the words of people who study the phenomenon,

the islanders had and still have "thrifty" genes, gens that make the

body extremely efficient at converting food calories to stored calories -

or, in other words, fat. A case of survival of the fattest?

Nowadays,

the islanders no longer face starvation. Indeed, quite the opposite.

They find themselves in a feast of carbohydrate, sugar, and fat. The

consequence? Body mass indices of over thirty. The story is similar to

the one of the Africans finding themselves for the first time in their

evolutionary history in a perpetual high-salt diet. What was a useful,

adaptive beneficial ability in the past environment can be a cost in a

new setting.

The thrifty-gene hypothesis has its

critics, as Elizabeth Genne-Bacon describes in her review of the

various ideas to explain obesity. However,

it appears that island animals might also have a thrifty metabolism. In

their case, they often have a low metabolic rate, instead of or in

addition to efficiently using food. They can afford a low metabolic rate

and lethargy, Brian McNab points out, because large predators are rare

on small islands.

Humankind: How Biology and Geography Shape Human Diversity. Harcourt, p. 112-113

If You Surround Yourself With Fat People Who Have Poor Eating Habits And Eat A Poor Diet You Too Will Become Fat!

|

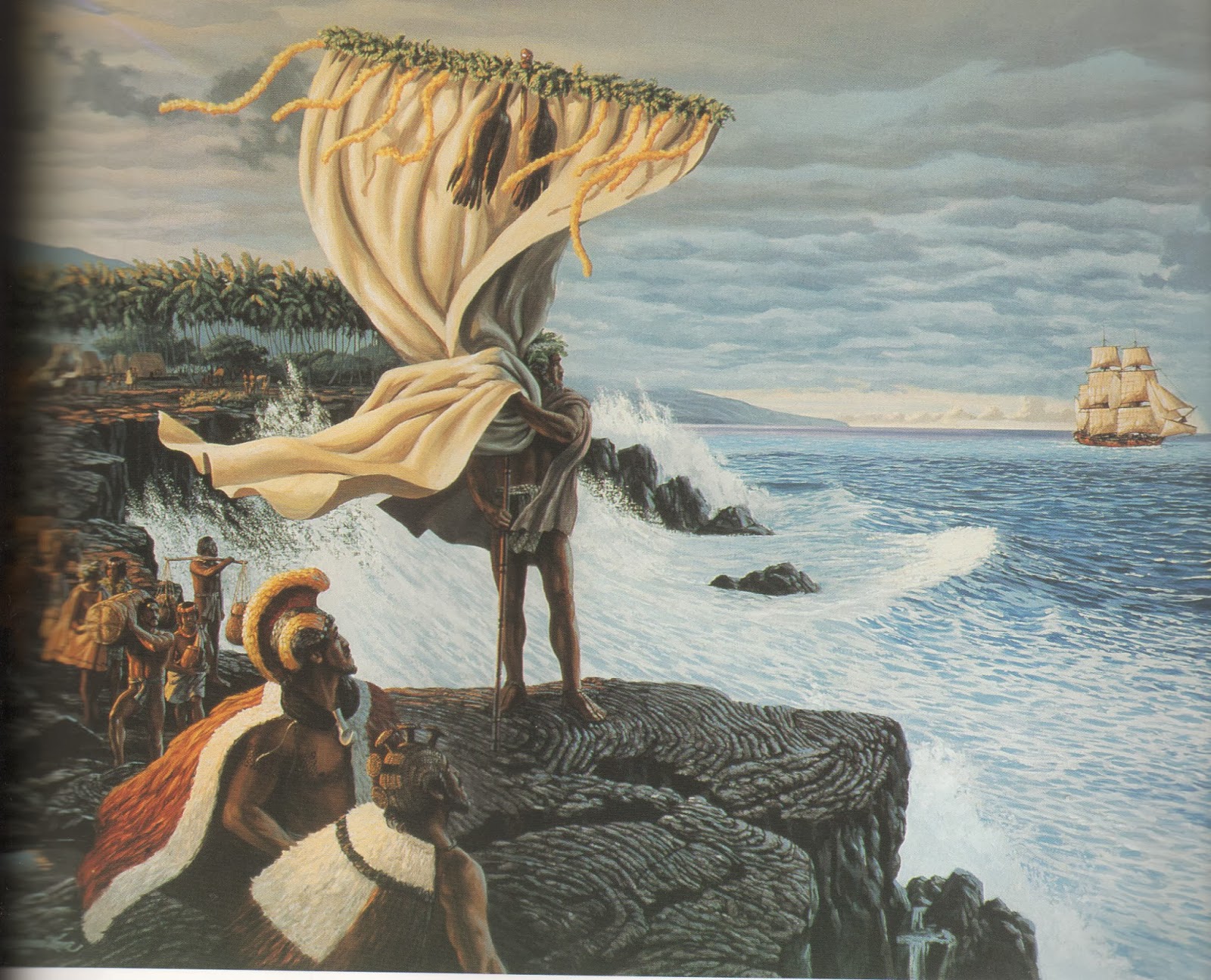

| Approximately 3,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesian people began colonizing the Pacific archipelagos. Starting at Tonga and proceeding stepwise eastward with large canoes designed for long voyages, they reached, by AD 1200, the extreme reaches of Polynesia, a triangle formed by Hawaii, Easter Island, and New Zealand. With this achievement of the Polynesian voyagers, the human conquest of Earth was complete. (The Social Conquest Of The World.) |

...

We don't deliberately breed humans for particular characteristics, we

don't (more fairly, we shouldn't) cull those who have them, and

generation times are long, making even the results of natural

experiments difficult to discern. Nonetheless, one natural experiment

has produced very obvious results in a relatively short period. In his

recent book The Lapita Peoples, my Berkeley colleague, Patrick V. Kirch,

has summarized the linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence,

showing that today's Polynesians derive from a population, or

populations, living off the eastern end of New Guinea. Over the past

4,000 years, they have spread out to cover a vast triangle of islands

from New Zealand in the south to Hawaii in the north and to Easter

Island in the east.

This expansion meant crossing thousands of miles

of ocean that could be chillingly cold at night, and doing so in large

outriggers for which upper-body strength would have been at a premium,

thus apparently selecting primarily for larger body size (Bergmann's

Rule) and, by extension, proportionately even larger upper bodies (there

is positive allometry between overall body size and upper-body size in

apes and ourselves). That big-bodied people live in the tropics at

first glance seems odd, but they are there. Jon Entine has noted that

more than fifty Polynesians have been in the National Football League,

making them by far its most "overrepresented minority." (Extended visits

in Auckland have left me [Sarich] noting to myself that "scrawny

Polynesian" would appear to be a null set.)

Race: The Reality of Human Differences. Sarich, Miele, p. 178-180.

http://www.silkassociates.com/information.php?info_id=8

READ THIS

http://www.silkassociates.com/information.php?info_id=9

READ THIS

0N 10 T0ES! REAL FOOL BLOODED HAWAIIANS ABOVE AND BELOW. THEY'RE BOTH EXAMPLES OF BERGMANN'S RULE!

This One Looks Like She Has Some White Genes, Tho! She Looks A Quarter White!

http://www.wsamoa.ws/index.php?m=83&s=&i=3860

Both cultural and biological adaptations were

required to make this crossing possible. The cultural innovations likely

included improvements in sailing technology and navigational expertise

and enhanced food preservation techniques. The biological adaptations

probably included the robust body build that facilitated paddling the

vessels and metabolic adaptations to dietary and cold stress. All of

these biological

adaptations may be the result of selection for a ‘thrifty phenotype’.

The Lapita sailing vessels had a large triangular sail that precluded

sailing too close to the wind.

The canoes sat low to the water, making paddling possible when winds

were too low or from the wrong direction. Skeletal remains from

Lapita sites and measurements on modern Polynesians depict a people of

substantial stature with broad shoulders and hips, and robust, long

limbs. The broad body, long limbs, and sizeable muscle mass are

particularly well suited to the biomechanics of paddling—a voyaging

strategy that only would have come into play in situations critical to

survival.

Thus, this body build would have had a strong selective advantage.

Houghton (1996) has modeled the severe cold stress that early Pacific

voyagers would have experienced. Maximum cold stress is achieved

overnight when moderately low temperatures, high wind chill, and wet

clothes and skin combine to produce substantial cold stress. Overnight

voyages would have been very rare prior to the “break out” from the

Solomon Islands. The same bodies that are well suited to paddling canoes

also have a favorable low surface area to body mass ratio, excellent

for conservation of body heat in cold stress. Again, a large, robust

body build would provided an advantage.

Traditionally the thrifty genotype argument has been used to explain

adaptation to periodic famine. In the case of the Pacific it has been

invoked as an adaptive response to caloric restriction associated with

voyaging and settlement of the islands (Bindon and Baker, 1997).

Metabolic efficiency in storage of excess calories is achieved through

over secretion of insulin which increases fat tissue formation and the

accumulation of an energy store.

This would also increase subcutaneous fat tissue which acts as an insulation against cold stress. It has been suggested,

however, that a population as well adapted to a marine environment as

the Lapita people were may not have suffered from extreme caloric

deprivation during voyaging and settlement.

Even so, their diet would have been drastically altered: lower

carbohydrate intake and an increase in protein intake. They would have

eaten through their supply of the poi-like fermented crops (taro,

breadfruit, banana) that they were carrying on their voyage and then had

to wait for new crops to grow before regaining their normal

carbohydrate intake. Several people have argued that the thrifty

genotype provides a metabolic adaptation to just such a high protein low

carbohydrate diet through the metabolic shifts involved in

hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance.

Recent research into thrifty genes has provided some clues that the

cold- and work-adapted body build and the metabolic shift to accommodate

dietary stress may be related. These adaptations may be the result of

mutations in the region of the insulin gene (INS), like the variable

number tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism near INS that causes increased transcription of both the INS gene and the close

Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 (IGF2) gene. Increasing transcription of

INS could generate high blood insulin levels (hyperinsulinemia) and

decrease sensitivity to insulin binding in peripheral cells (insulin

resistance). Meanwhile, high levels of IGF2 stimulate muscular and

skeletal growth predisposing to a large, robust body.

I do not mean to imply that this particular VNTR polymorphism represents

the thrifty gene, but it points to a possible area for exploration and

integrates the biological adaptations found in modern day Polynesians that appear to result from their voyaging history.

http://pvs.kcc.hawaii.edu/ike/moolelo/long_canoes.html

Emory published my statement of the idea in 1974.

In 1991, Philip Houghton of the University of Otago, New Zealand,

published a massive compilation of data which demonstrates conclusively

that the indigenous peoples of Remote Oceania (Polynesia, Micronesia,

and the more eastern part of Island Melanesia) have

physiques better suited to cold regions than to the tropics—larger,

more muscular, with more fat than any other tropical people. Observing

that for closely related mammals and birds, those living in cold regions

tend to have greater body mass than those of warm regions (Bergmann’s

rule), Houghton found the reason for the evolution of the Remote Oceania

physique in the chill of the open-ocean environment, which he amply

demonstrates with meteorological data. Houghton’ s conclusion:

“For Homo Sapiens, the wider Pacific, with its fluctuation

between hot and very cold conditions, is a unique environment. Neolithic

technology provided no useful protection against the wet—cold

conditions, and among the adaptive responses was selection for a large

muscular body. This change began in Island Melanesia.

...

When Proto-Polynesians departed from their Southeast Asian

homeland many thousands of years ago, their physiques may have been no

different that those of other tropical peoples. Their eastward drift

through the myriad islands of Indonesia and Melanesia may have been the

result of many explorations, each originating from a previously

established island settlement. Through findings of distinctive artifacts

archaeologists have traced the movement of Proto-Polynesians along the

Bismarck island chain off the northern coast of New Guinea and through

islands of Eastern Melanesia. Moving ever eastward into the vast ocean,

they honed their maritime skills as distances between islands increased,

sailing when the prevailing easterlies were replaced by more favorable

winds shifting from the north, south or west. Except for picking up

Melanesian genes along the fringe of Melanesia, their island world kept

them isolated. At some time more than 3,500 years ago, explorers

discovered uninhabited islands in what are now Samoa, Tonga, and the

small eastern islands of Fiji. Perhaps no more than a few canoe loads

arrived at what has been called “The Cradle of Polynesia.”

...

Imagine the following situation on any of the islands that

Proto-Polynesians settled on the long movement out from Asia: A chief

has reason to leave and search farther eastward for new land. Perhaps he

has lost a battle, or is a younger brother with no lands or

expectations, or a drought has brought the specter of famine. Let’s say

he is able to build or commandeer no more than four voyaging canoes. He

would favor companions who would give him the best chances of

survival—men able to wield a war club if a landing had to be forced on a

hostile shore, men and women large and strong enough to handle a canoe

in any weather. The canoe’s limitations would make it a silent but

powerful partner in deciding who would be selected. Call this “social

selection,” a preference for large size which seems to have echoed long

after voyaging was discontinued as a desirable trait, most notably in

chiefs.

During an arduous voyage, natural selection would likely cancel

out mistakes made on shore. Again the canoe would bring selective

pressures on those who would sail in it, favoring for survival those

with ample natural fat to insulate the body from the deadly chill of

wind evaporation upon spray-drenched skin.

And when an uninhabited island was discovered, those who settled

it would, as a small group in isolation, form the sole genetic pool for

future explorations. Such conditions, repeated over many voyages of

exploration and settlement, would have a cumulative impact on the

physical evolution of the people.

http://humanevolutionontrial.blogspot.com/2009/06/human-evolution-on-trial-pacific.html

http://humanevolutionontrial.blogspot.com/2009/06/human-evolution-on-trial-polynesian.html

http://humanevolutionontrial.blogspot.com/2009/06/human-evolution-on-trial-eastern.html

Near

Oceania laps at the eastern shores of New Guinea and stretches far

south and west into the Pacific. The heavily forested islands form a

voyaging corridor with predictable winds and currents, sheltered from

the tropical cyclone belts to the north and south. A canoe could sail in

summer from New Ireland or New Britain down the Solomons as far as

distant San Cristobal or Santa Ana, then return during the winter when

the winds shifted. By 25,000 years ago, late-Ice Age seafarers had

settled as far south and east as the Solomon Islands. They were hunters

and fisherfolk, clinging to the islands in small camps and rock

shelters. Judging from the lack of imported artifacts, each island

community seems to have kept to itself as they all adapted slowly to

their new homelands. But this isolation may be an allusion, for about

20,000 years ago, we have clear signs of contacts with others. Small

obsidian flakes now appear in settlements in the Bismark Archipelago,

toolmaking stone carried thither from Mopir and Talasea, on New Britain.

Since Talasea is a straight-line distance of at least 127 miles (350

kilometers) from the Bismarcks, it's clear that the islanders were

venturing long distances to obtain useful commodities. (We know this

because the distinctive trace elements of different obsidian sources can

be identified with spectrographs.)

As interisland

visits intensified, so did exploration. About 13,000 years ago, a canoe

from either the north coast of Sahul or the northern end of New Ireland

sailed 124 to 143 miles (200 to 230 kilometers) across the open Pacific

to invisible Manus Island. Thirty-seven to 56 miles (60 to 90

kilometers) of the passage involved sailing out of sight of land. As the

archaeologist Matthew Springs writes, "These would have been tense

hours or days on board that first voyage and the name of the Pleistocene

Columbus who led his crew will never be known." This epic voyage, known

only from evidence of human occupation on Manus dating to at least

13,000 years ago, leaves no doubt that late-Ice Age peoples in the

southwestern Pacific were capable of long ocean voyages.

These

explorers were without agriculture, but had hunted out so much island

quarry that they deliberately imported game. The islanders brought the

arboreal marsupial the gray cuscus (Phalanger orientalis) by canoe from

New Guinea to islands where they were unknown. Cuscus had arrived on New

Ireland by 15,000 years ago, bandicoots on the Admiralty Islands by

12,000 years before present, and wallabies on New Ireland by 7,500 years

ago. These seemingly haphazard attempts to increase food supplies on

relatively impoverished islands are unique in human history: for the

first time anywhere, people shifted food resources instead of moving to

them. Sometime later, farming began on the islands. New Guinea and the

Bismarcks were the places of origin for many tropical crops, among them

such later staples as taro, sugarcane, and some forms of banana. Fruit

trees were also important on the islands, with trees being cropped to

improve orchard yields. Domesticated plants allowed canoe skippers to

store food such as taro and yams for long voyages. Waterlogged remains

of such species found on New Britain date to at least 2250 B.C.E.

However, for all the voyaging, the human population of the southwest

Pacific was still tiny. This may have been because of endemic malaria,

for at least two species of malaria parasite had accompanied the first

human settlers when they crossed from Sunda to Sahul thousands of years

earlier. Only in the New Guinea highlands, above the habitats of malaria

mosquitoes, did denser farming populations flourish.

Island

life changed dramatically in about 1600 B.C.E., just when a massive

eruption of Mount Witari, on New Britain, smothered much of the island

in choking ash. The Witari cataclysm dwarfed the famous Krakatau Island

explosion of 1883, in the Sunda Strait off Indonesia, and must have

killed many of the island's inhabitants. Either just before or after the

disaster, strangers in much larger, more powerful canoes arrived in the

Bismarcks from the west.

The outriggers appear without

warning, large canoes with high-peaked, woven-fiber sails that seem to

move faster than the wind. Heavily laden, they come swiftly to land on a

beach by a stream some distance from the hunters' camp. Men, then women

and children, disembark cautiously, the males with weapons in hand. The

islanders watch silently from the forest's edge as the newcomers pull

their canoes clear of the breakers. They offload piles of taro roots and

yam plants, axes, adzes, and large pots. Two elders approach the canoes

cautiously, making gestures of friendship, chanting ritual greetings.

They're puzzled to discover that the strangers speak a different,

unintelligible language, but smiles and nods defuse the tension. In the

days that follow, the seafarers clear forest for taro plots, plant

crops, and build permanent houses, which are much more substantial than

the hunters' temporary shelters. It's clear that they are here to stay.

Except for some bartering of game meat for exotic shells, the contacts

between hunter and farmer are sporadic at best. Within a few weeks, the

hunters board their canoes and paddle away to forage

elsewhere.Meanwhile, more outriggers arrive from the east and establish

another village some distance away. However, some time later some of

these new arrivals also restlessly sail away to the next island on the

horizon, their crews as much at ease on the water as they are on the

land.

We archaeologists call these newcomers the Lapita

people, because a University of California at Berkeley anthropologist,

Edward W. Gifford, mounted an archaeological expedition to New

Caledonia, south and slightly east of Solomon Islands, in 1952, setting

to work at a site his team named Lapita, on the west coast. There he

unearthed a distinctive kind of stamped pottery radiocarbon-dated to

about 800 B.C.E., which was nearly identical to some exotic potsherds

found on Tonga, far to the east, thirty years earlier. Gifford realized

that his "Lapita ware" was a marker for deep-sea voyaging in the western

Pacific centuries earlier than had been assumed. Similar pottery soon

turned up throughout the southwest Pacific. Some of the vessels bear

intricate designs, including stylistic elaborations of human faces,

perhaps intended as symbolic depictions of cultural identity at a time

when Lapita people traveled over enormous distances. Today, we know of

more than two hundred radiocarbon-dated Lapita sites scattered from the

Bismarcks to the Solomons and far beyond into Remote Oceania - to Fiji,

Tonga, and Samoa, in Polynesia.

With so many dates and

this distinctive pottery, we can now track what was a rapid migration of

seafarers across Near Oceania - one of the most remarkable maritime

explorations in history. Quite where the Lapita people originated is

still a mystery, but it might have been from the northern Moluccas, in

eastern Indonesia, where clay vessels of similar shapes, but without the

stamped decoration, are known. The newcomers spoke an Austronesian

language, one of a vast family of such tongues that spread, perhaps from

Taiwan or some other location, more than halfway around the world, from

Madagascar, in the Indian Ocean, to Rapa Nui (Easter Island), deep in

the pacific. By 1500 B.C.E., they had settled throughout the Near

Oceania. For the next two or three centuries, the canoes stayed where

they were, the newcomers intermarrying with the indigenous populations.

Around

1200 B.C.E., a new chapter in long-distance voyaging began. For the

first time, canoes voyaged into Remote Oceania and its uninhabited

islands, beyond an invisible, and perhaps psychological, barrier at the

southeastern end of the Solomons that had stood for about 30,000 years.

They sailed first to the Santa Cruz Islands, which lie 235 miles (380

kilometers) southeast of San Cristobal. The journey from the southern

Solomons to the archipelago was simply a matter of using the seasonal

winds and following the east-west zenith path of the stars that passed

over both island groups. This technique, latitude sailing, was the

foundation of deepwater navigation as canoes sailed ever farther east.

Between about 1200 and 1100 B.C.E., other groups of Lapita people moved

into the Vanuatu archipelago, then on to New Caledonia.

Still

others sailed east from either Santa Cruz or Vanuatu against the

prevailing trades and currents. They crossed 530 miles (850 kilometers)

of unexplored ocean where there were no islands to stop and rest, until

they arrived in the Fiji archipelago, in around 800 B.C.E. From Fiji

came even more voyages eastward, threading through the numerous islands

of the Lau archipelago and from there to Samoa and Tonga, in what is now

known as western Polynesia. Without question, the Lapita colonists were

the ancestors of later Polynesian navigators who were to settle Hawaii,

Rapa Nui, and some of the remotest islands on earth many centuries

later.

We still know little about the Lapita people

or their voyages, except for the pathways left by their shell-decorated

potshreds. We can only guess at the ritual exchanges, the volatile

relationships - friendships and enmities - that defined their vast

island world. They were farmers, so, as crews zigzagged from island to

island, they carried seedlings, as well as chickens, dogs, and pigs, the

first domesticated animals to arrive in the southwestern Pacific. They

literally carried their own landscape with them. The new foods added

great flexibility to island economies that relied heavily on fish an

wild plant foods and some limited hunting. Lapita crops could be stored,

which tided people over from one season to the next. Above all, canoe

skippers could remain at sea for much longer, the pressing limitation

now being their ability to carry drinking water. A significant expansion

in longer-distance trade and in settlement and exploration of hitherto

uncolonized lands might have resulted.This expansion might also have

coincided with significant innovations in watercraft and in the

navigational lore that enabled sailors to make passages out of sight of

land for days on end.

Only rarely do these remarkable

seafarers come into historical focus. In about 1150 B.C.E., some Lapita

canoes landed at Teouma, a wide and shallow bay on the southwestern

shore of Efate Island, in the Vanuatu archipelago of the New Hebrides.

Here, freshwater came from a nearby stream, so the newcomers founded a

village nearby. They also established a cemetery on the coral-rubble

beach and in cavities in a nearby uplifted and volcanic-ash-covered

reef. Three archaeological field seasons in 2004-2006 recovered almost

fifty burials from the cemetery, which bring us face-to-face with a

Lapita society that clearly placed great emphasis on relationships with

their forebears. Remarkably, the skeletons are all headless, the skulls

having been detached by the mourners. Apparently, the living manipulated

the corpses of the deceased for some time after burial as part of their

transition to revered-ancestor status. Burial customs varied

considerably. For example, in one large grave, an adult male lay in a

grave with four others, three skulls and the jaw of a fourth person

lying on his chest. Isotopic readings from the bones and teeth of the

dead in the cemetery generally tell us that most of them subsisted on a

predominantly maritime diet, heavy on shellfish. But the four adult

males in the large grave produced distinctive readings associated with

diets more terrestrial than marine. Very likely these four individuals

migrated from to the island from elsewhere, a place where their drinking

water came from coastal rainfall near sea level, which is isotopically

distinct from Efate's spring-derived supply. Where these people came

from is still a mystery and may be difficult to pin down, because

shoreline environments are similar over a huge area of the western

Pacific. There of the four lay with their heads facing south, as if this

direction had some significance to the deceased. Perhaps they were the

first settlers, from a land with a more terrestrial diet. Alternatively,

they may represent people voyaging between communities to arrange

marriages, or for economic or political purposes.

One

possible clue may be the obsidian flakes found in the cemetery. We know

that obsidian from the Bismarck Archipelago traveled to Lapita

communities in the southwestern Solomons, to Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and

even Fiji. Perhaps the social networks created by these exchanges

linked islands out in the Pacific, over the open sea, up to as far as

125 miles (200 kilometers) away. Relatively few people were seafarers.

If the Teouma cemetery is any indication, then Lapita passage making was

as much a social phenomenon as a matter of colonization and trade. The

powerful social and ritual underpinnings of later interisland voyaging

might have originated with them.

None of the

Lapita voyages would have been possible without a legacy of seafaring

experience from the distant past and without major advances in canoe

technology, the means to navigate out of sight of land, and the ability

to stay at sea for days on end. For anything more than a day passage,

the canoes had to be capable of handling heavy weather and strong winds

with no convenient refugees nearby. They had to sail well, often in the

face of prevailing headwinds, and also be capable of carrying not only a

relatively large crew but also enough food and water. As we saw in

Chapter 2, a canoe sailing in waves is far more stable if it becomes a

platform rather than a single hull. Two ready solutions must have come

into play soon after people plied the waters off Sunda: outriggers and

double hulls. Of the two, the double-hulled canoe is the most practical

craft for offshore sailing, on account of both its load capacity and its

sailing qualities. Unfortunately, the last double-hulled canoes

disappeared at least a century ago, leaving us with nothing but drawings

by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artists, notably of elaborate

Tahitian war canoes, so we know little about these craft. We know from

modern experiments that double-hulled canoes were capable of sailing at a

reasonably close angle to the wind, perhaps as close as sixty degrees.

This would have made passages against prevailing trade winds entirely

practicable, if relatively slow. Thus, one always had the guarantee of

being able to return by turning in front of the wind.

...

The

Lapita ancestral voyages were far more than journeys of exploration.

They were deliberate voyages of colonization. We know this because the

earliest sites on previously uninhabited lands are clearly permanent

settlements, founded as colonies rather than transitory encampments. The

newcomers stayed for a generation or more, then some of them went to

sea again to find another new island. A rapid-fire sequence of Lapita

colonization continued for generations.

Why did Lapita

canoes keep on exploring ever outward into the unknown Pacific? Theories

abound. The founding populations must have been small, simply because

of the limited load-carrying capacity of their canoes. But the constant

expansion speaks to rapidly growing populations resulting from high

birth rates, low infant mortality, or increased life expectancy, perhaps

as a result of less malaria infestation. We do not know. But why would

people, having safely colonized a remote island with no close neighbors,

feel compelled to keep sailing southward and eastward? Many have argued

that population pressure was the cause, but many of the newly colonized

islands such as Efate had been large and uninhabited. Centuries would

have passed before population densities rose to crises levels. Thanks to

widespread finds of obsidian flakes, we know that the ancestral Lapita

were inveterate traders. Their explorations of the Bismarcks and other

closer islands might have been searches for new trading opportunities,

especially for obsidian outcrops and other valued commodities. However,

the farther out into the Pacific the canoes sailed, the fewer

opportunities there were for trade.

We are left with

intangible motivators, like social organization. According to linguists,

Proto-Oceanic words for such terms as kinship, social status, and so on

reveal a strong emphasis on birth inheritance in Laputa society.

Older

siblings ranked above younger ones. The firstborn inherited house

sites, gardens, and property - this apart from cherished ritual

privileges and all kinds of privileged knowledge. The University of

California at Berkeley archaeologist Patrick Kirch points out that

rivalries between older and younger brothers are a persistent theme in

Polynesian myths, which may perpetuate much earlier folklore. He writes,

"In such societies, junior siblings frequently adopt a strategy of

seeking new lands where they can found their own 'house' and the

lineage, lineage assuring their offspring access to quality resources."

Founders - the original colonists and discoverers - may have assumed

great prestige and importance in Lapita society, thereby providing a

powerful incentive for bold voyaging into the unknown. How, then,

did Lapita canoes navigate when out of sight of land? Even more

puzzling, how did the Lapita detect unknown islands beyond the horizon?

The art of navigating the open Pacific developed out of many centuries

of coasting and line-of-sight pilotage in Near Oceania. Once seafarers

had the watercraft and the motives, it was an easy matter to head

offshore, with the confidence both that they could return if need be and

that they could maintain a course by sun, moon, and the stars until

distant signs of land such as irregular wave patterns came into play.

Small wonder canoe pilots were highly respected members of society.

Colonists

revered their ancestors, whose names, like navigational lore, passed

down the generations: their deeds, fictional or otherwise, were a social

glue of oral traditions that linked isolated communities near and far.

When oceanic peoples moved from one island to another, they carried with

them a rich lode of knowledge about deities and culture heroes, about

human existence.

History and ritual beliefs passed by

word of mouth were one social bond, but just as important in practical,

day-to-day terms were the relationships between individuals and wider

kin groups living on other islands. No village was ever completely

self-sufficient. Quite apart from subsistence needs, the islanders

married outside their communities, which often meant moving to another

island. In time, durable kin ties maintained not only social links but

also complex trading networks that endured for centuries. Fine-grained

obsidian for tool making traveled in canoes from island to island. So

did rocks used to fashion stone axes and adzes used for cultivation;

seashells, including large ones used to make shell adzes; red feathers;

and all manner of objects, many of them having important prestige value -

to mention only a few items of exchange. All of this activity,

conducted between what were basically egalitarian groups, meant that

even sporadic contacts with other islands produced important social and

economic networks among individuals and groups that endured from one

generation to the next. Over time, their connections developed into

direct and indirect relationships that extended over hundreds of miles,

far over the horizon.

Material objects tell us nothing

of the complex relationships and social dynamics behind the voyages that

carried them far from their source. If historical Near Oceanian

societies are any guide, factionalism, ever-shifting alliances, and

sudden raids were part of island life, as were cherished relationships

between individuals living at considerable distance from one another,

who might meet face-to-face only once or twice in their lifetimes. Such

contacts, often endowed with profound spiritual meaning and frequently

reinforced by the exchange of valued objects, formed the umbrella for

much wider trading. That such contacts and relationships existed in

Lapita society seems unquestionable, for survival on remote islands

depended on relationships far beyond the confines of one's own village,

as it did right into modern times. The roots of today's elaborate

connections go back deep into the past, perhaps even to Lapita time,

albeit in different, probably simpler, forms. Most famous and enduring

of them all is the celebrated Kula ring of the Trobriand Islands. Such

networks, with their constant passages over open water, also contributed

significantly to the long process of decoding the ocean between the

islands.

...

Lapita canoes colonized a

mosaic of islands deep into Remote Oceania with remarkable speed. At

Samoa, the seafarers paused, for reasons that are little understood.

East of Samoa, landmasses are smaller, more isolated. But sometime in

the late first millenium C.E., voyaging resumed. By 1000 C.E., drawing

in the ancient voyaging expertise of their Lapita ancestors, people were

sailing to the Cook and Society islands, in the heart of Remote

Oceania. In western Polynesia, the traditions of interisland contact

expanded into a form of maritime empire centered on the large island of

Tongatapu. A sacred paramount chief, the Tu'i Tonga, presided over a

carefully controlled system of chiefly governance based on deliberately

nurtured connections across open water far beyond the Tonga archipelago,

into Fiji to the west and Samoa to the east. Long-distance voyaging

along familiar routes lay at the core of this "empire," combined with

strategic marriages that cemented ties over hundreds of miles.

Prestigious goods such as mats, feathers, sandalwood, bark cloth,

canoes, and pottery flowed into Tongatapu, the pinnacle of what became a

highly stratified, quite stable society. Tongan royal power depended on

a seamless knowledge of surrounding waters that blurred distinctions

between land and sea. Such blurring, inherited from Lapita ancestors,

was, here as everywhere, one of the keys to decoding the ocean.

...

Think

of a random pattern of islands scattered over thousands of square miles

of open water, most of them lying upwind against the prevailing trades,

and you can visualize the challenge facing those who first deciphered

the vast waters of eastern Polynesia beyond Samoa. These seagoing

journeys were that last great expansion of Homo sapines, a complex

diaspora that had begun south of the Sahara some 100,000 years ago. (The

date when our first modern ancestors left Africa is a matter of

debate.) Fully modern humans had settled in Southeast Asia by 60,000

years before the present, or perhaps earlier; had replaced Neanderthals

in Europe and Central Asia by 45,000 years ago; and had crossed into

North America by 15,000 years ago. As we've seen, by that time small

numbers of fisherfolk and seafarers had long since settled in New Guinea

and the southwestern Pacific - on the Solomon islands and in the

Bismarck Archipelago. After 1500 B.C.E., their successors, the Lapita

people, farmers and expert seafarers, navigated from island to island by

line of sight until they ventured offshore to the Santa Cruz Islands,

then ultimately to Tonga and Samoa, where they had arrived by 800 B.C.E.

There the seafarers paused for many centuries.

The

last pulse of the great diaspora reached far more than five hundred

islands in eastern Polynesia, an area of the Pacific larger than North

America - from Hawaii to Rapa Nui and as far south and west as New

Zealand and the Chatham Islands. Some canoes may even have reached South

America.

Tracing the voyages has engaged a small

regiment of scholars since Captain Cook's day. All manner of ingenious

approaches have been attempted to decipher the colonization of Remote

Oceania, including elaborate computer simulations and experimental

voyaging. The former are, of course, theoretical exercises that are only

as good as the data behind them, but they are strongly against one-way

voyages. The simulations also highlight the increasing difficulty of

voyaging and navigation as one sailed east. When sailing into unknown

waters, the pilots probably went by indirect routes if they could, as

well as by some form of latitude-like sailing using the stars. As in

Lapita explorations, each canoe traveled onto the teeth of the

prevailing easterly winds, taking advantage of periods when the trades

were down. This ancient, conservative strategy allowed them to discover

new lands over the horizon while always knowing that they could return

safely home.

We'll never know much about these voyages.

Many of the probes must never have sighted land. One imagines two

canoes sailing close to one another, food and water running low, the

pilots talking quietly across the water. They look at the sky, see

tell-tale trade-wind clouds, a sign the winds are changing. After

careful deliberation, they reverse course, using familiar

constellations, to return home safely. On many occasions, too, the

canoes would never return, victims of sever squalls or prolonged calms,

of starvation. If they did sight land and found it suitable for

settlement, the canoes would have to return home first. They knew well

that repeated visits would be needed to establish a viable island

community.

The initial explorations might have involved

just men, but deliberate colonization would have brought women,

children, crops, and animals to the newly discovered land. Perhaps later

voyages would have carried skilled artisans, as well as single women to

maintain a viable sex ratio if too many people died. Such voyages were

long and dangerous to undertake, so it's hardly surprising that the

tempo of passage making slowed once the new community flourished. Oral

traditions suggest that later voyages were matters of piety or social

connection. For instance, canoes from all over Polynesia made

pilgrimages to the Taputapuatea temple, on Raiatea in the Societies, the

religious center of eastern Polynesia. Here priests and navigators

gathered to make scarifices to the gods and to exchange genealogical and

navigational lore. Adventurous Tahitian chiefs occasionally sailed to

Hawaii to marry into noble lineages or to visit long-departed kin. But

eventually the voyages ceased as new priorities at home revolved around

war and the shifting sands of competing alliances.

When

did the voyages take place, and how long did colonization take? Dating

them was largely a matter of guesswork until the University of Chicago

chemist Willard Libby and his research team developed radiocarbon dating

in the late 1940s. For the first time, there was a way of dating the

settlement of Polynesian islands - or so it seemed. By 1993, 147 dates

had produced a mosaic timescale for the first settlement, with the

colonization of the Society Islands and surrounding archipelagos in the

900-950 C.E. range. This chronology appeared just before accelerator

mass spectrometry (AMS) refind carbon dating dramatically. Now

excavators could obtain dates from samples as small as individual seeds

adhering to a pot.

The rules of the dating game have

changed completely since AMS arrived. The newer dates, a tenfold

increase over 1993, are much more accurate, their contexts more

carefully researched. Instead of looking at individual dates, one can

treat them as statistical groups. A recent study of the first

settlements uses no fewer than 1,434 samples from at least forty-five

eastern Polynesian islands, carefully appraised for accuracy and for

their associations with human activity or with what are called

commensals, animals like the Pacific rat that lived only with humans. We

now have an even shorter chronology of remarkable precision that spans

thousands of square miles of the Pacific. The 1,434 dates revealed a

dramatic burst of ocean voyaging.

For about 1,800 years

after arriving there, in about 800 B.C.E., the Lapita ancestors of the

Polynesians stayed around Samoa and the Tonga archipelago. Then,

suddenly, between about 1000 and 1300 C.E., Polynesian seafarers

discovered, and usually colonized, nearly every other island in the

eastern Pacific in a relatively narrow time span.

The

colonization dates speak for themselves. A wave of canoes arrived in the

Society Islands between 1025 and 1121 C.E., the Marquesas between 1200

and 1400. Other voyages reached New Zealand between 1230 and 1280, Rapa

Nui between 1200 and 1263, and Hawaii between 1219 and 1269. Some

Polynesian pilots might have even have sailed to South America and back.

The rapid pace of colonization might account for the remarkable

similarities in artifacts such as adzes and fishhooks in places as

widely separated as the Societies, the Marquesas, and New Zealand. A

mere three centuries of ocean voyaging wrote the last chapter in the

100,000-year journey of Homo sapiens across the world. By the time

European voyagers arrived a few centuries later, farming, imported

animals, and promiscuous hunting had changed the environments of

Polynesia's islands beyond recognition.

...

How

did the Polynesians find their way over trackless oceans? The answer

lies in the heavens, as visible as sea is on land. A Polynesian

navigator acquired his knowledge by apprenticeship to experienced pilots

when he was still a child. The late Mau Piailug, a master navigator

from the Caroline Islands, in Micronesia, started his apprenticeship at

age five, listening to his grandfather talking about passages he made.

As Piailug grew older, he accompanied his grandfather on interisland

voyages, learning about stars, swell patterns, and birds. When he was a

teenager, Piailug studied with an uncle who taught him not only

practical knowledge but also complex magical and spiritual lore. At age

fifteen, he was initiated as a palu, a navigator, and subject to intense

oral drilling day and night for a month as he memorized star tracks

across the heavens. Only then was he allowed to sail offshore as a

pilot.

Mau Piailug might have lived out his life in

quiet isolation, had it not been for the English physician David Henry

Lewis, an expert small-boat sailor who abandoned medicine for the sea.

He sailed through the Carolines in the 1960s, learned something of

traditional navigational practices long assumed to be forgotten, then

piloted his catamaran from Tahiti to New Zealand with the help of a

Micronesian pilot, steering by the stars just as the ancients had done.

Subsequently, Lewis apprenticed himself to Melanesian and Micronesian

navigators from the Caroline islands and Tonga. Meanwhile, in the late

1960s, the American anthropologist Ben Finnery began long-term

experiments with replicas of ancient Polynesian canoes. Hokule'a,

designed by Hawaiian Herb Kawainui Kane, was 62 feet (19 meters) long,

with double hulls and two crab-claw-shaped sails. Finney, Mau Piailug,

and a mainly Hawaiian crew sailed Hokule'a from Hawaii to Tahiti and

back in 1976. They followed this journey with a two-year voyage around

the Pacific using only indigenous pilotage. Thanks to the successful

Hokule's experiments and other replica voyages, ancient Polynesian

navigational skills have been preserved for posterity.

...

The

great voyages were long over when Bougainville, Cook, and other

European explorers arrived in Polynesia in the mid-eighteenth century.

However, the deeds of the great pilots linger in Polynesian oral

traditions as part of the common beliefs and values transmitted from one

generation to the next. Great culture heroes like Maui, the father of

lands, and Rata, an expert canoe builder, figure in historical

narratives throughout much of Polynesia and may date back to Lapita

times. Maui snared the sun, fished up islands, and obtained fire, a

symbol of the human struggle to harness the forces of nature. Rata, the

canoe builder, perhaps himself a voyager, figures in traditions that may

be at least 3,000 years old. The oral traditions preserve the names of

the great navigators like Hiro. He was born in the Societies and, as an

adult, acquired a passion for sailing, stealing, and womanizing. He is

said to have sailed to the Marquesas, Hawaii, the Australs, and Rapa Nui

in large canoes with sewn planks. Whoever the navigators were, they

carried far more than sailing lore with them. Generic place names

meaning "passage" and "reef" traveled around them throughout Polynesia.

They designed small islands at the entrances to natural harbors as

places of sanctuary for visiting canoes waiting to see if it was safe to

go ashore. The mosaic of oral memories provides some names, some shared

cultural traditions, but does not answer the question of questions: Why

did small numbers of people suddenly decide to sail over the horizon in

search of new lands?

What prompted such deliberate

voyages? Were they quests for religious enlightenment, for the realm of

the ancestors, or simply a reflection of those most human of all

qualities, curiosity and restlessness? We don't know. Whatever the

motivation, to sail eastward toward sunrise into unknown waters was a

hazardous enterprise, given the prevailing northeasterly trades. To

cover any distance would require setting sail when the trades were down,

something that happened for only a few weeks a year between January and

March, except when El Ninos dampened the trades. It might be no

coincidence that the eastern voyages occurred during a documented spike

of El Nino activity during the early second millennium. Even with

unexpected breaks from the wind, the social reasons for taking off into

the unknown must have been compelling. We can only speculate about

them.

Like their Lapita forebearers, early

Polynesian societies placed great emphasis on birth order, inheritance,

and kin ties. As was the case farther west, older siblings outranked

their younger brothers and sisters. Oral traditions are full of

rivalries between older and younger brothers. Some siblings sailed away

to seek new homelands, where they could found their own privileged

lineage and pass land to their offspring. Such ventures were

expensive but prestigious, requiring superlative navigational skills

acquired over many years. Thus, successful voyages over the horizon

acquired a mystique that was passed down the generations, not

necessarily because their leaders were exceptional pilots but because

they became founders of descent lines firmly anchored in new lands.

Long-distance

voyaging was a privileged activity. Most Polynesians stayed at home,

fishing in lagoons and cultivating their gardens. Cultivable acreage was

the basis for social life, even on the larger islands. The social

structure associated with agriculture revolved around inheritance and

access to the land. Birth order was all-important. So the driving force

behind colonization of Remote Oceania may have been a quest for land and

the privileges of inheritance. Prestige and power also came from

maritime expertise, from knowledge of a deciphered ocean, To those who

traveled across them Polynesian waters became not a barrier but a

network of watery highways that connected one's island to many others.

With

these pathways came economic, social, and other ties, some of which

endured for generations, while others were but transitory. Soon after

initial settlement, a complex network of interconnections linked island

to island, settlement to settlement, individual to individual -

economic, ritual, and social ties maintained by navigators and seafarers

over many generations. Just as with the Kula, contacts with other

islands resulted in trade and exchange, and also sometimes in marriage

partners. Much of the contact was with near neighbors, with whom people

shared a common history as well as close cultural and other ties. This

meant, for example, that the Tongans sailed regularly to Samoa and Fiji.

|

| Walk The Plank Pimp |

...Elsewhere,

navigational traditions virtually disappeared until the

twentieth-century revival. They were alive and well in 1769, when James

Cook arrived at Matavai Bay, on Tahiti, to observe the passage of Venus

across the sun. There he met a navigator-priest named Tupaia and other

pilots, who astounded him with their knowledge of neighboring islands.

He wrote: "Of these they know a very large part by their Names and the

clever ones among them will tell you in what part of the heavens they

are to be seen in any month when they are above their horizon." Cook,

himself a consummate navigator, learned that Tupaia knew the names and

locations of more than a hundred islands around Tahiti. He compiled a

chart of seventy-four islands from Tupaia's verbal accounts of their

bearings on the horizon. They ranged from Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga in the

west to some of the Marquesas, Australs, and Tuamotus in the east, a

huge swath of the Pacific. Tupaia might not have visited them all, but

he had the knowledge (using the word in the same sense as London

cabdrivers do). Much of his information was probably in the form of oral

traditions, some of which must have dated back to the much earlier days

of regular long-distance voyaging. Subsequently, Tupaia guided Cook's

ship some 500 miles (800 kilometers) from Tahiti through the Society

Islands and from Raiatea to Australs. With each destination, he always

"pointed to the part of the heavens where each isle was situated,

mentioning at the same time that it was either larger or smaller than

Taheitee, and likewise whether it was high or low, whether it was

peopled or not." According to Tupaia, the longest a canoe could stay at

sea without reprovisioning was about twenty days.

Another

explorer, Spaniard Domingo de Bonechea, carried Puhoro, a Tuamotan

navigator, on a voyage to Lima in 1775. During the voyage, Puhoro

dictated a list of fifteen islands east of Tahiti, including most of the

Tuamotus, and twenty-seven to the west, both in the Societies and the

Cooks, He also enumerated the topography and reefs of each island, the

main products, the hostility or friendliness of the inhabitants, and the

number of days needed to sail to each one, and he described the sixteen

points of the wind compass used in conjunction with star paths.

Once

the template of surrounding waters lay in navigators' minds, the

routines of passage making were well established in seeming perpetuity,

despite a virtual cessation of very long trips. Dangerous voyages

lasting weeks gave way to shorter journeys that were part of the

tapestry of everyday existence. People sought wives on neighboring

islands, visited shrines, and traded foodstuffs. As island populations

grew, different communities acquired reputations for such items as red

feathers used in important rituals, shells for adze blades, and ax

stone. We know from sourcing studies of basalt adze and ax blades (akin

to those from obsidian) that there were repeated contacts between many

island groups. Basalt found in a rock shelter on Mangaia Island came

from American Samoa, nearly 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) away. Adze

stone from the Marquesas traveled by canoe to Moorea, in the Society

Islands, to mention only two examples of such contacts documented from

finds in archaeological sites. Trade networks ebbed and flowed,

prospered, then ceased to operate. For generations, the inhabitants of

the southern Cooks relied on exotic pearl shell and other materials for

both ornaments and such prosaic artifacts as shell fishhooks. After

regular contacts with other islands ceased, the villagers turned to

inferior local materials instead.

The arrival of humans

on the Pacific islands led to immediate, often fundamental

environmental changes - deforestation from agriculture, widespread

erosion, and the rapid extinction of many intensively hunted sea and

land birds as well as indigenous animals such as the giant turtles of

Efate Island, in the Vanuatu archipelago, some of them up to 8 feet (2.4

meters) long. Many islands in Remote Oceania abounded in birds, fish,

and shellfish and enjoyed salubrious, malaria-free climates but lacked

vegetable foods until farmers arrived. When people started clearing land

and planting, the islands rapidly became largely cultural environments,

whose productivity varied widely with soil and rainfall. Ingenious and

highly productive farming systems, combined with fishing, produced large

food surpluses in many places, despite rising population densities. The

wetter landscapes of the Society Islands supported dense farming

populations, while the ancient taro pond fields of Hawaii fed thousands

of people and are in use to this day.

Inevitably,

political and ritual power passed to those who owned the best land. By

1600 C.E., some Polynesian societies had developed into elaborate

chiefdoms headed by small elites of chiefs, navigators, and priests,

especially in areas where wet, swamp-based agriculture was possible.

Inevitably, the escalating demands of chiefs and priests questing for

ever more prestige threatened the fine line between subsistence and

surplus. Rivalries led to war. In the Society Islands, chiefdoms turned

in on themselves as they juggled slippery alliances and warfare in

vicious competition for good farming land and for political and ritual

power. The inhabitants were aware of islands over the horizon, of a much

wider world, but their cultural horizons were confined more to

landscape than to seascape, as if the broad expanses of the ocean were

no longer relevant.

The Society Islands maintained at

least tenuous contacts with outlying archipelagos, but the Hawaiians

flourished in isolation after some centuries of sporadic voyaging.

Judging from esoterica like the designs of shell fishhooks and adzes and

also linguistic similarities, it seems likely that the first settlers

in Hawaii came from the Marquesas. Hawaiian oral traditions speak of a

subsequent "voyaging period" in which great navigators like Mo'ikeha and

Pa'ao sailed to a mythic homeland, "Kahiki' - perhaps Tahiti - and

back. The great passages ceased after 1300. Complete isolation ensued,

except for the symbolic return of an anthropomorphic god, Lono, who was

said to journey from Kahiki each year to renew the land. When James Cook

anchored off Kauai in 1778, the local people thought his ship was a

floating island. The islanders learned that he had come from Tahiti, so

they assumed he was Lono, who had traveled there many generations

earlier and promised to return. Cook promptly became a great ancestor.

By this time, at least 250,000 people lived on the Hawaiian Islands,

under the rule of powerful chiefs.

Isolation was no

barrier to Polynesian navigators, who sailed enormous distances - not

only more than 2,500 (4,000 kilometers) to Hawaii but to New Zealand and

Rapa Nui, and perhaps even farther afield. Thirteenth-century

Polynesian navigators from the Cooks, the Societies, or the Australs are

said to have followed cuckoos to New Zealand (Aotearoa), the last, and

the largest, Pacific landmass they colonized. A pleasing legend, for the

long-tailed cuckoo indeed flies south from Polynesia to New Zealand in

September. There must have been more than a few voyages to achieve

lasting settlement in what was a heavily forested, unfamiliar

environment. Then the voyages ceased, as they did elsewhere. A now

isolated Maori society developed into a mosaic of competitive, warlike

kingdoms, but their oral traditions list the achievements of twenty or

more generations, recounted with the aid of notched sticks. What is

actual history ultimately merges into the mythological, but, like other

Polynesians, they have a profound sense of their maritime ancestry and a

strong bond with the great ocean, which their ancestors traversed

centuries ago.

|

| ...the mass of archaeological evidence and oral accounts of war before European contact...makes it far-fetched to maintain that people were traditionally peaceful until those evil Europeans arrived and messed things up. There can be no doubt that European contacts or other forms of state government in the long run almost always end or reduce warfare, because all state governments don't want wars disrupting the administration of their territory. Studies of ethnographically observed cases make clear that, in the short run, the initiation of European contact may either increase or decrease fighting, for reasons that include European-introduced weaponry, diseases, trade opportunities, and increases or decreases in food supply. A well understood example of a short-term increase in fighting as a result of European contact is provided by New Zealand's original Polynesian inhabitants, the Maori, who had settled in New Zealand by around AD 1200. Archaeological excavations of Maori forts attest to widespread Maori warfare long before European arrival. Accounts of the first European explorers from 1642 onwards, and of the first European settlers from the 1790s onwards, describe Maori killing Europeans as well as each other. From about 1818 to 1835 two products introduced by Europeans triggered a transient surge in the deadliness of Maori warfare, in an episode known in New Zealand history as the Musket Wars. One factor was of course the introduction of muskets, with which Maori could kill each other far more efficiently than they had previously been able to do when armed just with clubs. The other factor may initially surprise you: potatoes, which we don't normally imagine as a major promoter of war. But it turns out that the duration and size of Maori expeditions to attack other Maori groups had been limited by the amount of food that could be brought along to feed the warriors. The original Maori staple food was sweet potatoes. Potatoes introduced by Europeans (although originating in South America) are more productive in New Zealand than are sweet potatoes, yield bigger food surpluses, and permitted sending out bigger raiding expeditions for longer times than had been possible for traditional Maori depending upon sweet potatoes. After potatoes' arrival, Maori canoe-borne expeditions to enslave or kill other Maori broke all previous Maori distance records by covering distances of as much as a thousand miles. At first only the few tribes living in areas with resident European traders could acquire muskets, which they used to destroy tribes without muskets. As muskets spread, the Musket Wars rose to a peak until all surviving tribes had muskets, whereupon there were no more musket-less tribes to offer defenseless targets, and the Musket Wars faded away. (The World Until Yesterday. Jared Diamond.) |

Aotearoa, some 600 miles (1,000

kilometers) southwest of Fiji and Tonga, was an enormous target by

Polynesian standards, very different from the tiny islands of the east,

such as Rapa Nui. Some canoes were sailing there by about 1200-1269 C.E.

The human population grew steadily in isolation, achieving

sustainability by using ingenious agricultural methods in face of the

deforestation caused by the depredations of rats that arrived in the

canoes, as well as humans. The carving of the great ancestral statues

(moai) and the building of temple platforms using communal labor were

important ways of maintaining social cohesion, which fell apart after

Europeans arrived.

Were Aotearoa and Rapa Nui the last

frontiers of Polynesian exploration? Or did canoes venture 2,200 miles

(3,500 kilometers) farther east, to the Americas, a distance roughly

equivalent to that from the Society Islands to Hawaii? In theory, canoe

navigators who had located tiny specks on the ocean were perfectly

capable of sailing to the massive continents to the east. According to

archaeologist Geoffrey Irwin, the most likely routes to South America

would have been from southeast Polynesia, passing south of the

high-pressure area that endures in the eastern South Pacific before

sailing to the coast ahead of southerly winds, using a northbound

current. Similar conditions would have pertained for canoes sailing

northward from Hawaii until clear of the North Pacific High, at which

point they could turn eastward, as many sailing yachts do today. In both

cases, returning canoes could ride the prevailing trades. But did they

actually do it? No one has yet found Polynesian artifacts anywhere on

American coasts, despite claims to the contrary. We know that the

American sweet potato and the bottle gourd reached Polynesia, the latter

as much as a thousand years ago. Coconuts, which originated in

Southeast Asia and Melanesia, were established on the west coast of

Panama before Europeans arrived. The chances of any of these plants

having drifted east or west for months, then germinating, are

infinitesimal, so canoes may well have carried them to new homelands. A

potential smoking gun comes from an unlikely source: chicken bones. The

mitochondrial DNA from chicken bones found on Tonga and Samoa is

identical to that from chicken fragments found at a coastal settlement

named El Arenal-1, in south-central Chile, dating to 1321-1407 C.E.,

nearly a century before Columbus landed in the Bahamas and before the

time of the great voyages. Perhaps, then, Polynesian canoes reached

South America soon after the colonization of Remote Oceania, bringing

chickens with them. Perhaps, they picked up plants like sweet potatoes

and bottle gourds and brought them back to Polynesia.

If

such voyages took place - and the genetic science seems impeccable -

what was the nature of the contacts between Polynesians and Americans?

Were they fleeting or more lasting? Did any of the visitors from beyond

the horizon stay in Chile or elsewhere and marry into the local

population? We may never know, but there is nothing in the story of the

human decipherment of the Pacific that suggest that such voyages were

impossible. We should never forget that as long as the land and the

ocean are seen as one, people will venture offshore and decode the most

demanding of seascapes.

Beyond the Blue Horizon.

Fagan, p. 34-72.

http://lens.auckland.ac.nz/images/3/31/Pacific_Migration_Seminar_Paper.pdf

http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&frm=1&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCkQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.researchgate.net%2Fpublication%2F220042228_Rethinking_Polynesian_Origins_A_West-Polynesian_Triple-I_Model%2Ffile%2F79e415074cb654466a.pdf&ei=V6iPUrPYK4b3oASZ_4HgDA&usg=AFQjCNHJ8AAR1IycMuB1KiA3rZiYU9bOvQ&bvm=bv.56988011,d.cGU

http://class.csueastbay.edu/faculty/gmiller/3710/DNA_PDFS/mtDNA/mtDNA-Polynesia.pdf

http://www.anthropology.hawaii.edu/people/faculty/Hunt/pdfs/Barnes_and_Hunt.pdf

http://www.clarku.edu/~jborgatt/smfa_Oceania/Polynesia.pdf

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/02/110203124726.htm

In fact, the DNA of current Polynesians can be traced back to

migrants from the Asian mainland who had already settled in islands

close to New Guinea some 6-8,000 years ago.

...This means we can be confident that the Polynesian

population -- at least on the female side -- came from people who

arrived in the Bismarck Archipelago of Papua New Guinea thousands of

years before the supposed migration from Taiwan took place."

Nevertheless, most linguists maintain that the Polynesian languages

are part of the Austronesian language family which originates in Taiwan.

And most archaeologists see evidence for a Southeast Asian influence on

the appearance of the Lapita culture in the Bismarck Archipelago around

3,500 years ago. Characterised by distinctive dentate stamped ceramics

and obsidian tools, Lapita is also a marker for the earliest settlers of

Polynesia.

Professor Richards and co-researcher Dr Pedro Soares (now at the

University of Porto), argue that the linguistic and cultural connections

are due to smaller migratory movements from Taiwan that did not leave

any substantial genetic impact on the pre-existing population.

"Although our results throw out the likelihood of any maternal

ancestry in Taiwan for the Polynesians, they don't preclude the

possibility of a Taiwanese linguistic or cultural influence on the

Bismarck Archipelago at that time," explains Professor Richards. "In

fact, some minor mitochondrial lineages back up this idea.

It seems

likely there was a 'voyaging corridor' between the islands of Southeast

Asia and the Bismarck Archipelago carrying maritime traders who brought

their language and artefacts and perhaps helped to create the impetus

for the migration into the Pacific.

http://www.foxnews.com/story/2007/03/21/pig-dna-suggests-alternate-origin-malayo-polynesian-people/

"People tend to think of colonization and culture as moving in a

single unit," he said, "but with history we've learned that the simplest

answer is rarely the right one."

...

The Lapita people, "might have just come together in New Guinea from

different parts of Asia, with separate groups bringing different parts

of the culture with them," he said, and moving on to more outer lying

islands from there.

|

| One Of The Polynesian Founder Populations May Have Come From The Moluccas MothaFucca. (Polynesia

Was Settled Within The Past 4,000 Years (The Ethnic Groups Of Polynesia