I'M GOING

TO MAKE THIS QUICK. THE FIRST FIVE PAGES HAVE TO DO WITH EMPATHY AND

THE STORY OF THE GOOD SAMARITAN (RELATE THIS TO WHAT I'VE WRITTEN ON

ANOTHER POST ABOUT PEOPLE AVOIDING BUMS). BENEATH THIS ARE PARAGRAPHS

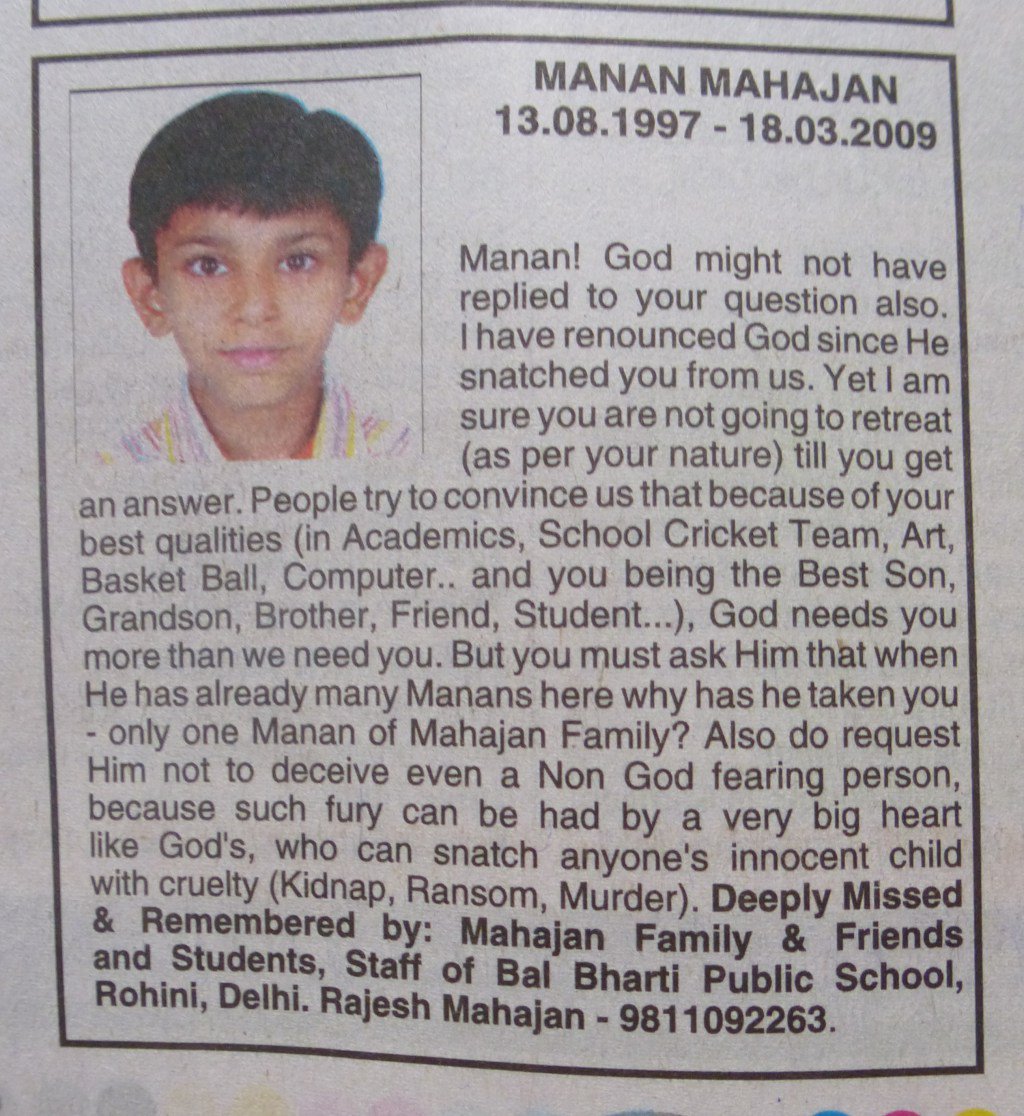

CONCERNING RELIGION (WHY CERTAIN ATHEISTS ARE THE WAY THEY ARE, WHY

EMOTION DICTATES OUR REASON AND BELIEFS, AND HOW HUMANS EVOLVED TO BELIEVE IN

RELIGION BUT NOT SCIENCE).BUT BEFORE YOU GET TO ALL OF THAT READ THESE PAGES FROM DAVID EAGLEMAN'S THE BRAIN REGARDING THE HUMAN TENDENCY TO DEHUMANIZE THOSE WHO WE PERCEIVE AS BEING UNLIKE US AND BELONGING TO AN OUT-GROUP!

We Reserve Empathy For Those In Our In-Group! Those Who We Perceive As Being Unlike Us And From A Social Or Cultural Or Racial Group Unlike Ours Don't Deserve Our Empathy And Compassion. At Least, That's How We Unconsciously Reason And Justify Our Behavior Towards Outsiders.

Etop Udo-Ema Retweeted

On the court takes care of itself. Off the court is where character is built. No other program in the nation doing this at a high level. Sponsor feeding the homeless and advocate sponsorship for 10 deserving HS programs. Good luck keeping up

#GiveBack #ExpectNothingInReturn

#GiveBack #ExpectNothingInReturn

#GiveBack #ExpectNothingInReturn

#GiveBack #ExpectNothingInReturnHE MAY BE MAKING HIS PLAYERS FEED THE HOMELESS, BUT IS HE MAKING HIS PLAYERS CHANGE THEIR MINDSET AND THE WAY THEY THINK ABOUT THE HOMELESS. IS HE MAKING HIS PLAYERS LOOK AT THE HOMELESS IN A MORE COMPASSIONATE AND HUMANISTIC LIGHT? IS HE MAKING HIS PLAYERS LOOK AT THE HOMELESS AS FELLOW HUMANS WHO DESERVE DIGNITY AND RESPECT? I DON'T THINK SO. SO ALL OF THIS "WORK" THAT HE AND HIS PLAYER DO FOR THE HOMELESS IS BENEFITING THEM (HE AND HIS PLAYERS) MORE THAN THE HOMELESS! IT'S BENEFITING HE AND HIS PLAYERS BY BOOSTING THEIR IMAGE, WHICH MAKES THEM MORE SEXUALLY AND SOCIALLY APPEALING! WHAT A FUCKIN' CONMAN THAT TREE TOP EDAMAMI GUY IS!

This was of course a lie, because I am not religious at all. The man, a pastor, was taken aback, probably more by my accent than by my answer. He must have realized that converting a European to his brand of religion was going to be a challenge, so he walked back to his car, but not without handing me a business card in case I'd change my mind. A day that had begun so promisingly now left me feeling like I might go straight to hell.

I was raised Catholic. Not just a little bit Catholic, like my wife, Catherine. When she was young, many Catholics in France already barely went to church, except for the big three: baptism, marriage, and funeral. And only the middle one was by choice. By contrast, in the southern Netherlands - known as "below the rivers" - Catholicism was important during my youth. It defined us, setting us apart from the above-the-rivers Protestants. Every Sunday morning, we went to church in our best clothes, we received catechism at school, we sang, prayed, and confessed, and a vicar or bishop was present at every official occasion to dispense holy water (which we children happily imitated at home with a toilet brush). We were Catholic through and through.

But I am not anymore. In my interactions with religious and non-religious people alike, I now draw a sharp line, based not on what exactly they believe but on their level of dogmatism. I consider dogmatism a far greater threat than religion per se. I am particularly curious why anyone would drop religion while retaining the blinkers sometimes associated with it. Why are the "neo-atheists" of today so obsessed with God's nonexistence that they go on media rampages, wear T-shirts proclaiming their absence of belief, or call for a militant atheism? What does atheism have to offer that's worth fighting for? As one philosopher put it, being a militant atheist is like "sleeping furiously."

THE MONAHANS

I was too restless as a boy to sit through an entire mass. It was akin to aversion training. I looked at it like a puppet show with a totally predictable story line. The only aspect I really liked was the music. I still love masses, passions, requiems, and cantatas and don't really understand why Johann Sebastian Bach ever wrote his secular cantatas, which are so obviously inferior. But other than developing an appreciation of the majestic church music of Bach, Mozart, Haydn, and others, for which I remain eternally grateful, I never felt any attraction to religion and never talked to God or felt a special relationship. After I left home for the university, at the age of seventeen, I quickly lost any remnant of religiosity. No more church for me. It was hardly a conscious decision, certainly not one I recall agonizing over. I was surrounded by other ex-Catholics, but we rarely addressed religious topics except to make fun of popes, priests, processions, and the like. It was only when I moved to a northern city that I noticed the tortuous relationship some people develop with religion.

Much of postwar Dutch literature is written by ex-Protestants bitter about their severe upbringing. "Whatever is not commanded is forbidden" was the rule of the Reformed Church. Its insistence on frugality, black dress code, continuous fight against temptations of the flesh, frequent scripture readings at the family table, and its punitive God - all contributed greatly to Dutch literature. I have tried to read these books, but have never gotten very far: too depressing! The church community kept a close eye on everyone and was quick to accuse. I have heard shocking real-life accounts of weddings at which the bride and groom left in tears after a sermon about the punishment awaiting sinners. Even at funerals, fire and brimstone might be directed at the deceased in his grave so that his widow and everybody else knew exactly where he'd be going. Uplifting stuff.

In contrast, if the local priest visited our home, he would count on a cigar and a glass of jenever (a sort of gin) - everyone knew that the clergy enjoyed the good life. Religion did come with restrictions, especially reproductive ones (contraception being wrong), but hell was mentioned far less than heaven. Southerners pride themselves on their bon vivant attitude to life, claiming that there's nothing wrong with a bit of enjoyment. From the northern perspective, we must have looked positively immoral, with beer, sex, dancing, and good food being part of life. This explains a story I heard once from an Indian Hindu who married a Dutch Calvinist woman from the north. Although the woman's parents didn't have the faintest idea what a Hindu was, they were relieved that their new son-in-law was at least not Catholic. For them, belief in multiple deities was secondary to the heretic and sinful ways of their next-door religion.

The southern attitude is recognizable in Pieter Brueghel's and Bosch's paintings, some of which bring to mind Carnival, the beginning of Lent. Carnival is big in Den Bosch, when the city is known as Oeteldonk, and also celebrated in nearby Catholic Germany, in cities like Cologne and Aachen, where Bosch's family came from (his father's name, "van Aken," referred to the latter city). Bosch must have been well versed in the zany Carnival atmosphere, and its suspension of class distinctions behind anonymous masks. Just like Mardi Gras in New Orleans, Carnival is deep down a giant party of role reversal and social freedom. The Garden of Earthly Delights achieves the same by depicting everyone in his or her birthday suit. I am convinced that Bosch intended this as a sign of liberty rather than the debauchery some have read into it.

Possibly, the religion one leaves behind carries over into the sort of atheism one embraces. If religion has little grip on one's life, apostasy is no big deal and there will be few lingering effects. Hence the general apathy of my generation of ex-Catholics, which grew up with criticism of the Vatican by our parents' generation in a culture that diluted religious dogma with an appreciation of life's pleasures. Culture matters, because Catholics who grew up in papist enclaves above the river tell me that their upbringing was as strict as that of the Reformed households around them. Religion and culture interact to such a degree that a Catholic from France is not really the same as one from the southern Netherlands, who in turn is not the same as one from Mexico. Crawling on bleeding knees up the steps of the cathedral to ask the Virgin of Guadalupe for forgiveness is not something any of us would consider. I have also heard American Catholics emphasize guilt in ways that I absolutely can't relate to. It is therefore as much for cultural as religious reasons that southern ex-Catholics look back with so much less bitterness at their religious background than northern ex-Protestants.

Egbert Ribberinkk and Dick Houtman, two Dutch sociologists, who classify themselves, respectively, as "too much of a believer to be an atheist" and "too much of a nonbeliever to be an atheist," distinguish two kinds of atheists. Those in one group are uninterested in exploring their outlook and even less in defending it. These atheists think that both faith and its absence are private matters. They respect everyone's choice, and feel no need to bother others with theirs. Those in the other group are vehemently opposed to religion and resent its privileges in society. These atheists don't think that disbelief should be kept locked up in the closet. They speak of "coming out," a terminology borrowed from the gay movement, as if their nonreligiousness was a forbidden secret that they now want to share with the world. The difference between the two kinds boils down to the privacy of their outlook.

I like this analysis better than the usual approach to secularization, which just counts how many people believe and how many don't. It may one day help to test my thesis that activist atheism reflects trauma. The stricter one's religious background, the greater the need to go against it and to replace old securities with new ones.

Religion looms as large as an elephant in the United States, to the point that being nonreligious is about the biggest handicap a politician running for office can have, bigger than being gay, unmarried, thrice married, or black. This is upsetting, of course, and explains why atheists have become so vocal in demanding their place at the table. They prod the elephant to see whether they can get it to make some room. But the elephant also defines them, because what would be the point of atheism in the absence of religion?

As if eager to provide comic relief from this mismatched battle, American television occasionally summarizes it in its own you-can't-make-this-stuff-up way. The O'Reilly Factor on Fox News invited David Silverman, president of the American Atheist Group, to discuss billboards proclaiming religion a "scam." Throughout the interview, Silverman kept up a congenial face, complaining that there was absolutely no reason to be troubled, since all that his billboards do is tell the truth: "Everybody knows religion is a scam!" Bill O'Reilly, a Catholic, expressed his disagreement and clarified why religion is not a scam "Tide goes in, tide goes out. Never a miscommunication. You can't explain that." This was the first time I had heard the tides being used as proof of God. It looked like a comedy sketch with one smiling actor telling believers that they are too stupid to see that religion is a fraud, but that it would be silly for them to take offense, while the other proposes the rise and fall of the oceans as evidence for a supernatural power, as if gravity and planetary rotation can't handle the job.

All I get out of such exchanges is the confirmation that believers will say anything to defend their faith and that some atheists have turned evangelical. Nothing new about the first, but atheists' zeal keeps surprising me. Why "sleep furiously" unless there are inner demons to be kept at bay? In the same way that firefighters are sometimes stealth arsonists and homophobes closet homosexuals, do some atheists secretly long for the certitude of religion? Take Christopher Hitchens, the late British author of God Is Not Great. Hitchens was outraged by the dogmatism of religion, yet he himself moved from Marxism (he was a Trotskyist) to Greek Orthodox Christianity, then to American Neo-Conservatism, followed by an "antitheist" stance that blamed all of the world's troubles on religion. Hitchens thus swung from the left to the right, from anti-Vietnam War to cheerleader of the Iraq War, and from pro to contra God. He ended up favoring Dick Cheney over Mother Teresa.

Some people crave dogma, yet have trouble deciding on its contents. They become serial dogmatists. Hitchens added, "There are days when I miss my old convictions as if they were an amputated limb," thus implying that he had entered a new life stage marked by doubt and reflection. Yet, all he seemed to have done was sprout a fresh dogmatic limb.

Dogmatists have one advantage: they are poor listeners. This ensures sparkling conversations when different kinds of them get together the way male birds gather at "leks" to display splendid plumage for visiting females. It almost makes one believe in the "argumentative theory," according to which human reasoning didn't evolve for the sake of truth, but rather to shine in discussion. Universities everywhere set up crowd-pleasing debates between religious and antireligious intellectual "giants."

The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates. de Waal, p. 83-89.

My first experience with proselytizing was almost too comical to be true. At the time, I had a room on the fourth floor of a university dormitory, in Groningen. On morning, I heard a knock on my door, and two young American Mormons in jackets and ties stood in front of me. Curious to hear about their faith, I invited them in. They proceeded to set up an easel and a board on which they pasted felt figures and text labels to explain the story of an ordinarily named American, who had seen the Lord in a pillar of light. Later, he was led by an angel to holy texts on golden plates.

All of this happened just over a century ago. I listened to their incredible tale and was just about to ask how this Joseph Smith convinced others of his special encounter, when we were rudely interrupted. I often left a window open to let Tjan, my pet jackdaw, fly in and out. He was free outside, but would come in before dark to be fed and locked up for the night. While the two young men patiently recounted God's appearance in a cave, Tjan sailed into the room looking for a landing spot. He went for the highest point, which was the head of one of the Mormons standing in front of his board. A large black bird landing on him was the last thing he'd expected. I saw the panic on his face and quickly tried to assure him that this was just Tjan, a bird with a name, who wouldn't hurt anyone. I have never seen two people pack up so quickly: they were gone in no time, out the door, running for the elevator. While they collected their things, I heard them talk of the "devil."

My having spoiled Tjan as a baby with the fattest earthworms I could dig up made him extra large for his species. He was such a curious and intelligent character, who'd fly above me on strolls through the park. But of course he was black, noisy, and crow-like, reminding the Mormons of a creature that might steal their souls. As a result, they never got to answer my question, nor did they have a chance to explain how Smith translated the golden plates engraved with "reformed Egyptian" by gazing at "peep stones" placed in the bottom of his hat. Smith was smart enough to empathize with his skeptics: "If I had not experienced what I have, I couldn't have believed it myself."

So, why did people believe him? Smith met with a great deal of derision and hostility (he was killed by a lynch mob at the age of thirty-eight), but the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints now counts 14 million followers. It is obvious that believers are not looking for evidence, because the only item that might have been helpful, the set of golden plates, had to be returned to the angel. People simply believe because the y want to. This applies to all religions. Faith is driven by attraction to certain persons, stories, rituals, and values. It fulfills emotional needs, such as the need for security and authority and the desire to belong. Theology is secondary and evidence tertiary. I agree that what the faithful are asked to believe can be rather preposterous, but atheists surely won't succeed in talking people out of their faith by mocking the veracity of their holy books or by comparing their God with the Flying Spaghetti Monster. The specific contents of beliefs are hardly at issue if the overarching goal is a sense of social and moral communion. To borrow from a tithe by the novelist Amy Tan, to criticize faith is like trying to save fish from drowning. There's no point in catching believers out of the lake to tell them what is best for them while putting them out on the bank, where they flop around until they expire. They were in the lake for a reason.

Accepting that faith is driven by values and desires makes at once for a great contrast with science, but also exposes common ground, since science is less fact-driven than is widely assumed. Don't get me wrong, science produces great results. It has no competition when it comes to understanding physical reality, but science is also often, like religion, based on what we want to believe. Scientists are human, and humans are driven by what psychologists call "confirmation biases" (we love evidence that supports our view) and "disconfirmation biases" (we disparage evidence that undermines our view). That scientists systematically resist new discoveries was already the topic of a 1961 article in the illustrious pages of Science, which added the mischievous subheading "This source of resistance has yet to be given the scrutiny accorded religious and ideological sources."

...

My own story concerns the discovery, in the mid-1970s, that chimpanzees make up after fights by kissing and embracing their opponents. Reconciliation behavior has now been demonstrated in many primates, but when one of my students needed to defend a study of this behavior before a committee of psychologists, she got an earful. We had naively assumed that these psychologists, who knew only rats, would have no opinion about primates, yet they were adamant that reconciliation in animals was out of the question. It didn't fit their thinking, which excluded emotions, social relationships, and everything else that makes animals interesting. I tried to change their minds by inviting them to the zoo where I worked so that they could see for themselves what chimpanzees do after fights. To this proposal, however, they replied bafflingly, "What good would it do to see the actual animals? It will be easier for us to stay objective without this influence."

It is said that the ancient king of Sardis complained that "men's ears are less credulous than their eyes." Only here it was reversed: these scientists feared that their eyes might tell them something they didn't want to hear. Like the rest of humanity, scientists apply fight-or-flight responses to data: they go for the familiar and avoid the unfamiliar. I have to think of this each time I hear neo-atheists claim that their God denial makes them smarter than believers and rational like scientists. They like to present themselves as emotion free, "just the facts, ma'am" kind of thinkers. In a column in USA Today, Jerry Coyne, a fellow biologist and self-declared "gnu-atheist" (yes, "gnu" as in "wildebeest," which is Dutch for "wild beast"), called faith and science utterly incompatible "for precisely the same reason that irrationality and rationality are." He then proceeded to draw little aureoles around the heads of scientists:

Science operates by using evidence and reason. Doubt is prized, authority rejected. No finding is deemed "true" - a notion that's always provisional - unless it's repeated and verified by others. We scientists are always asking ourselves, "How can I find out whether I'm wrong?"Oh, how I wish I had colleagues like Coyne! Having spent all my life among academics, I can tell you that hearing how wrong they are is about as high on their priority list as finding a cockroach in their coffee. The typical scientist has made an interesting discovery early on in his or her career, followed by a lifetime of making sure that everyone else admires his or her contribution and that no one questions it. There is no poorer company than an aging scientist who has failed to achieve these objectives. Academics have petty jealousies, cling to their views long after they have become obsolete, and are upset every time something new comes along that they failed to anticipate. Original ideas invite ridicule, or are rejected as ill informed. As neuroscience pioneer Michael GazzaniGga complained in a recent interview,

There is a profound inhibitory effect on new ideas by people and ideas that "got there first," telling their story over and over while new observations struggle up from the bottom. The old line that human knowledge advances one funeral at a time seems to be so true!This is more like the scientists I know. Authority outweighs evidence, at least for as long as the authority lives. There is no lack of historical examples, such as resistance to the wave theory of light, to Pasteur's discovery discovery of fermentation, to continental drift, and to Rontgen's announcement of X-rays, which was initially declared a hoax. Resistance to change is also visible when science continues to cling to unsupported paradigms, such as Rorschach inkblot test, or keeps touting the selfishness of organisms despite contrary evidence. Scientists praise the "plausibility" and "beauty" of theories, making value judgements on the basis of how they think things work, or ought to work. Science is in fact so value laden that Albert Einstein denied that all we do is observe and measure, saying that what we think exists is a produce almost as much of theory as of observation. When theories change, observations follow suit.

If faith makes people buy an entire package of myths and values without asking too many questions, scientists are only slightly better. We also buy into a certain outlook without critically weighing each and every underlying assumption and often turn a deaf ear to evidence that doesn't fit. We may even, like the psychologists on my student's committee, deliberately turn down a chance to get enlightened. But even if scientists are hardly more rational than believers, and even if the entire notion of unsentimental rationality is based on a giant misunderstanding (we cannot even think without emotions), there is one major difference between science and religion. This difference resides not in the individual practitioners but in their culture. Science is a collective enterprise with rules of engagement that allow the whole to make progress even if its parts drag their feet.

What science does best is to incite competition among ideas. Science instigates a sort of natural selection, so that only the most viable ideas survive and reproduce...In comparison, religion is static. It does change with a changing society, but rarely as a result of evidence. This sets up a potential conflict with science...

The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates. de Waal, p. 95-100.

...

Perhaps the question can be answered on a smaller scale, as in a study of the longevity of nineteenth-century communities in the United States. Communities based on a secular ideology, such as collectivism, disintegrated much faster than those based on religious principles. For every year that communities lasted, religious ones were four times as likely to survive than their secular counterparts. Sharing a religion dramatically raises trust. We know the huge bonding effect of coordinated practices, such as praying together and carrying out the same rituals. This relates to the primate principle that acting together improves relationships, ranging from monkeys' preferring human experimenters who imitate them to varsity rowers' gaining physical resistance (such as a higher pain threshold) from exercising as a team rather than on their own. Joint action may stimulate endorphin release, as has also been suggested for other bonding mechanisms, such as joint laughter. These positive effects of synchronization help explain the cohesiveness of religions and their effect on social stability.

Durkheim dubbed the benefits derived from belonging to a religion its "secular utility." He was convinced that something as pervasive and ubiquitous as religion must serve a purpose - not a higher purpose, but a social one. The biologist David Sloan Wilson, who analyzed the data on early Christians, agrees in that he sees religion as an adaptation that permits human groups to function harmoniously: "Religions exist primarily for people to achieve together what they cannot achieve alone."

Religious community building comes naturally to us. In fact, given how commonly religion is pitted against science, it is good to remember the tremendous advantage religion enjoys. Science is an artificial, contrived achievement, whereas religion comes as easily to us as walking or breathing. This has been pointed out by many authors, from the American primatologist Barbara King, who in Evolving God relates the drive to religion to our desire to belong, to the French anthropologist Pascal Boyer, who views religion as an intuitive capacity:

Scientific research and theorizing has appeared only in very few human societies...The results of scientific research may be well-known, but the whole intellectual style that is required to achieve them is really difficult to acquire. By contrast, religious representations have appeared in all human groups that we know, they are easily acquired, they are maintained effortlessly and they seem accessible to all members of a group, regardless of intelligence or training. As Robert McCauley points out,...religious representations are highly natural to human beings, while science is quite clearly unnatural. That is, the former goes with the grain of our evolved intuitions, while the latter requires that we suspend, or even contradict most of our common ways of thinking.Contrast the ease with which children adopt religion with the long and laborious road young people travel to achieve a Ph.D. around the age of thirty. McCauley, a philosopher colleague of mine at Emory, told me that if he had to choose which of the two would survive if society collapsed, he'd put his money on religion rather than science: "Religion overwhelmingly depends upon what I'm calling natural cognition, thinking that is automatic, that is not conscious for the most part." McCauley contrasts this with science, which is "conscious, usually in the form of language. It's slow, it's deliberative."

Imagine, we put a few dozen children on an island without adults. What would happen? William Golding thought he knew, giving us savagery and murder in Lord of the Flies. This may have been a great extrapolation from life at English boarding schools, but there is no sherd of evidence that this is what children left to their own devices will do. When four-to five-year-old children are left alone in a room, they tend to negotiate with each other by means of moral terminology such as "That's not fair!" or "Why don't you give her some of your toys?" No one knows what children would do if left alone for a much longer time, but they would definitely form a dominance hierarchy. Young animals, whether goslings or puppies, quickly battle it out to establish a pecking order, and children do the same. I remember the pale faces of psychology students steeped in academic egalitarianism, upset at seeing young children beat up on each other on the first day of preschool. We are a hierarchical primate, and, however much we try to camouflage it, it comes out early in life.

The children on the island might also enter the symbolic domain. They'd probably develop language in the same way that Nicaraguan deaf children, in the 1980s, began communicating in a simple sign language that outsiders couldn't follow. Many other aspects would develop as well, such as culture. The children would transmit habits and knowledge and show conformism in the tools they made or how they greeted each other. They'd also have property rights and tensions over ownership. Finally, they would undoubtedly develop religion. We don't know what kind, but they would believe in supernatural forces, perhaps personalized ones, like gods, and develop rituals to appease them and bend them to their will.

The one thing the children would never develop is science. By all accounts, science is only a few thousand years old, hence it appeared extremely late in human history. It is a true accomplishment, a critically important one, yet it would be naive to put it on the same level as religion. The war between science and religion is, to put it in biblical terms, one between David and Goliath. Religion has always been with us and is unlikely to ever go away, since it is part of our social skin. Science is rather like a coat that we have recently bought. We always risk losing it or throwing it away. The antiscience forces in society require constant vigilance, given how fragile science is compared with religion. To contrast the two as if they are on equal footing and in competition is a curious misrepresentation explainable only by reducing science and religion to sources of knowledge about the same phenomena. Only then could anyone argue that if one of the two is right, the other must be wrong.

When it comes down to knowledge of the physical world, the choice is obvious. I can't fathom why in this day and age, with everyone walking around with laptops and traveling through the air, we still need to defend science. Consider how far biomedical science has come, and how much longer we live as a result. Isn't it obvious that science is a superior way of finding out how things work, where humans come from, or how the universe arose? I am among scientists every day, and there is nothing more addictive than the thrill of discovery. True, plenty of mysteries are left, but science offers the only realistic hope of solving them. Those who present religion as a source of this kind of knowledge, and stick to age-old stories despite the avalanche of new information, deserve all the scorn they invite. But I also consider this particular collision between science and religion a mere sideshow. Religion is much more than belief. The question is not so much whether religion is true or false, but how it shapes our lives, and what might possibly take its place if we were to get rid of it the way an Aztec priest rips the beating heart out of a virgin. What could fill the gaping hole and take over the removed organ's functions?

The Bonobo and the Atheist: In Search of Humanism Among the Primates. de Waal, p. 211-216.

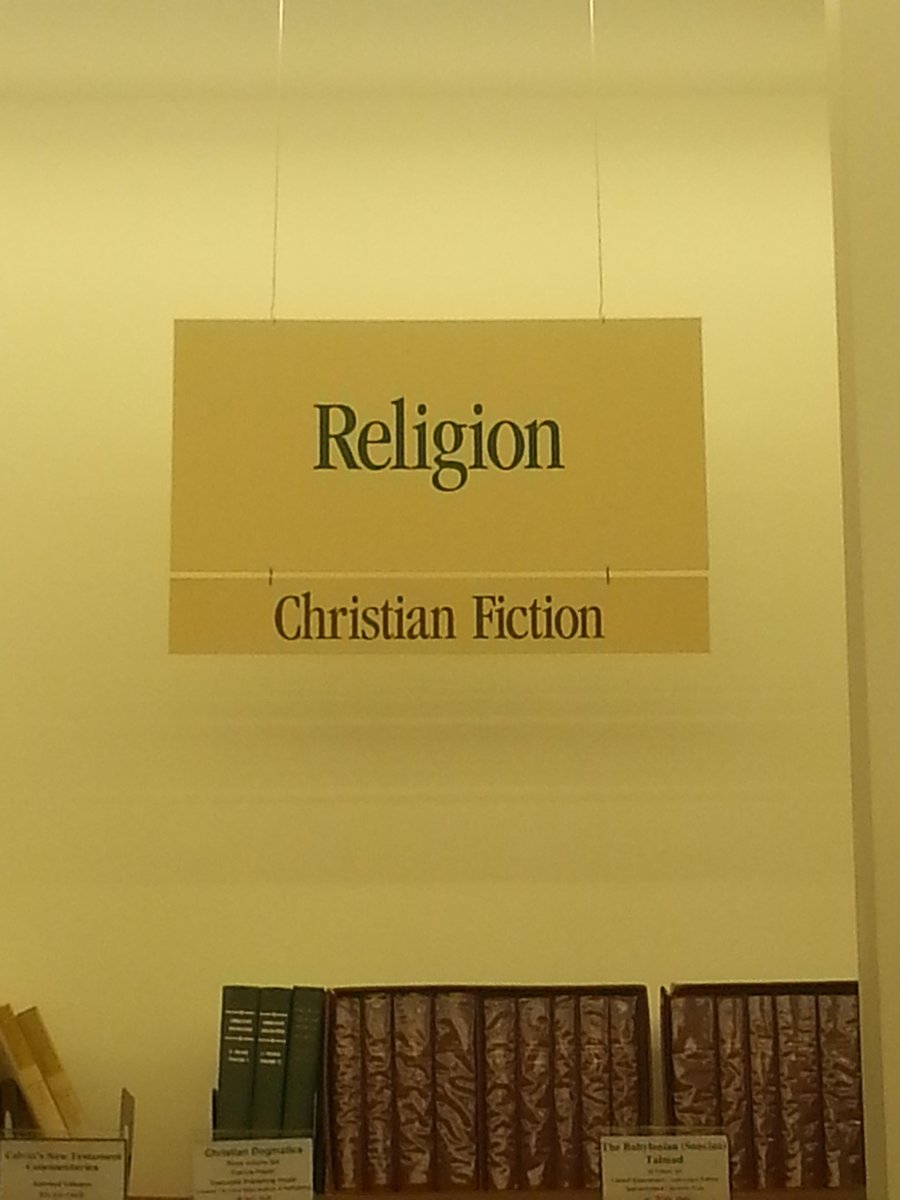

"NO RELIGION IS THE NEW RELIGION...SHE SAID SHE DON'T BELIEVE IN G0D!" - Peter Dagampat Ph.D.

FICTION! THAT'S WHAT THE BIBLE CONSISTS OF!