The President Did What?

Lecture Four: Behavioral Genetics and Evolutionary Psychology

Late in 1986, the Minnesota group had completed assembling its data for a major paper, the concordance of a broad range of personality traits between sets of separated twins, now totaling forty-four. The paper also included data on 331 reared-together twins, 217 identical and 114 fraternal. A trait that showed one of the highest levels of heritability, .60, was traditionalism, or a willingness to yield to authority. The only one of these traits to show a higher heritability was social potency, which included such characteristics as assertiveness, drive for leadership, and a taste for attention. A surprisingly high genetic component - a .55 concordance - was found in the ability to be enthralled by an aesthetic experience such as listening to a symphonic concert.

Good news for the environmentalists was that one important trait, one of the species' most appealing, appeared to have little genetic basis: the need for social intimacy and loving relationships. The heritability figure for this trait was .29, putting it just under Bouchard's somewhat arbitrary threshold of genetic significance. If you were warm and loving, you probably came from a warm and loving home. But here it should be remembered that if a trait has a high heritability, say above .60, that still leaves room for many people who came by the trait not by their genes but by environmental influences.

"I'M COLD AND HATEFUL!" - Peter Dagampat Ph.D.

Other noteworthy numbers emerged. In five of the categories tested - stress reaction, aggression, control, traditionalism, and absorption - the separated twins tested slightly more concordant than the identical twins reared together. As this oddity is not mentioned in the paper, the Minnesota team appeared to give it little significance. No trait showed zero heritability, and most were in the .45 to .60 range.

In this comprehensive paper on personality, the Minnesota team could not resist taking shots at earlier psychological studies that measured similarities in twins reared together and showed the twins to be far more similar to each other than they were to nontwin siblings. Oblivious to the possibility of genetic influence, the studies attributed those similarities to environmental factors such as twins' influences on each other, more similar treatment by others, and greater expectations from families of similar behavior from twins than from brothers and sisters. All of these explanations were wiped out when the twins studied were raised separately.

It is understandable that Bouchard, who was usually diplomatic and nonconfrontational in putting forth his orthodoxy-shattering conclusions, would sound a note of exasperation about these gene-blind studies. He knew that the researchers behind them, all trained psychologists who knew of the high level of genes shared by twins (50 percent or 100 percent), were so grounded in the prevailing dogma of their profession that they never thought to look outside the environment for explanations of why twins were more similar in personality than other siblings. Bouchard made clear that he found this an astounding misassumption. By ignoring the possibility of genetic influences on personality in setting up these studies, by placing genes off-limits, psychology's policy-makers assured none would be found.

Minnesota's paper on personality traits repeatedly reproached earlier studies aimed exclusively at the environment, saying that because they focus on "social class, children rearing patterns and other common-environment characteristics of intact biological families, [these studies] cannot be decisive because they confound genetic and environmental factors." The phrase cannot be decisive was a polite way of saying they tell us nothing. It was as though scientists undertook studies of the makeup of water with the proviso that only hydrogen be looked at; oxygen was off bounds.

The personality paper concludes with a subdued summation of the Minnesota team's startling findings: "It seems reasonable, therefore, to conclude that personality differences are more influenced by genetic diversity than by environmental diversity." The paper also asserted that shared family environment turned out to have a negligible effect on personality. Social closeness was the only trait that appeared to be mainly a product of family environment.

When this important paper was concluded, it was sent out for review prior to publication in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. The review process by other, unrelated experts in the field is a standard procedure for scientific papers and in complex studies like Minnesota's about personality measurements can take up to a year to complete. Participants in the review process often discuss their findings with colleagues at other universities; only in unusual situations is tight secrecy maintained. Still, it is rare for the results to reach the press until the paper is reviewed and published.

A prolonged incubation period prior to publication was not to be the case with Minnesota's findings on personality. The results leaked out and were proclaimed in the lead story of the "Science Times" section of the New York Times on December 2, 1986, a full year before the paper itself was published. The article ran with the headline MAJOR PERSONALITY STUDY FINDS THAT TRAITS ARE MOSTLY INHERITED. Daniel Goleman, who later wrote Emotional Intelligence, started his article with straightforward declaration of the findings principal import: "The genetic makeup of a child is a stronger influence on personality than child rearing, according to the first study to examine identical twins reared in separate families."

In a sample of parent–offspring, sibling–sibling, and second-degree relative pairs, who rated their Big Five personality traits and life satisfaction and were each rated by an independent informant, we found that parent–offspring and sibling correlations were about one third higher than typically shown (r ≈ .20). Based on the ordinary relative comparisons, the heritability of personality traits and life satisfaction was about 40%, compared with about 26% typical to self-report studies. Life satisfaction was as heritable as personality traits, sharing about 80% of its genetic variance with neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness..

Thus, typical self-report studies have likely underestimated the narrow-sense heritability of personality traits by about 15% points, or about 35% in relative terms. At least a third of personality traits’ and life satisfaction’s genetic variance may be nonadditive, hence not making most relatives much more similar than strangers and contributing little to our understanding of the genetic sources of personality trait variance

...

We provide further evidence that growing up together does not make people more similar. Besides twin comparisons and adoption studies, this finding is yet another piece of evidence that the experiences people share as a result of growing up together have no lasting effect on their personality traits. Instead, the nontwin relatives’ similarity likely results from additive genetic transmission. This yet again defies the lay intuition that upbringing shapes people’s personality traits

Goleman referred to 350 pairs of twins studied by the Minnesota group and later added that, of these, forty-four pairs were identical twins raised in different homes. He described the study's design and gave samples of the questions aimed at measuring personality ("True or False? When I work with other I like to take charge?"). Early in the piece, Goleman stated the overall results: "For most of the traits measured, more than half the variability was found to be due to heredity, leaving less than half determined by the influence of parents, home environment and other experiences in life."

In a box running beside the article's first column, Goleman listed the eleven traits examined and gave the heritability figure for each. The highest were social potency (.61) and traditionalism (.60). Five were between .50 and .60: stress reaction, absorption, alienation, well-being, and harm avoidance. Three were between .40 and .50: aggression, achievement, and control. The last, social closeness, just squeaked above the significance level with a revised figure of .33. A pair of warm, loving twins must have arrived in Minneapolis to boost the earlier figure.

The article included quotes from other experts that underscored the significance of the findings. Jerome Kagan, the distinguished Harvard psychologist, was quoted as saying, "If in fact twins reared apart are that similar, this study is extremely important for understanding how personality is shaped." This was a generous comment since Kagan himself, with thirty years of developmental research behind him, had been a leader in the struggle to understand how personality was shaped.

Most of the papers that flowed from the Minnesota Twin project in the late eighties appeared in professional journals of the psychology field. While these periodicals were respected, the time had come to break out of the hermetic world of psychology and put forth a broad summary of the Minnesota findings in a publication that covered important advances in all the sciences. In the United States, the premier venue for such reports was Science magazine. Bouchard had met the editor, Daniel Koshland, at a conference in 1984, when Koshland was a biochemist at Berkeley. They had had a conversation about the Minnesota project and Bouchard had obliged Koshland's request to be kept informed about the twin research. In 1989, four years after becoming editor of Science, Koshland approached Bouchard about writing a paper that would summarize his results to date. Bouchard was delighted.

The paper, published in 1990, shows none of the reticence of the earlier papers and starts off with a trumpet blast about the finding most likely to ignite controversy, the high heritability of I.Q. The figure was slightly lower than the earlier one, .70, but still high enough to alarm the antigenes holdouts. The paper went on to summarize Minnesota's other findings, concluding with a body blow to the environmentalists: On a number of measures of personality, temperament, interest, and attitudes, the twins reared apart measured about the same as the twins reared together.

Having set forth the explosive implication that rearing environments apparently made little difference in personality formation, the authors moved quickly to soften their claims. Within the paper's initial abstract, they suggest an explanation sure to be more palatable to traditional environmentalists. "It is a plausible hypothesis that genetic differences affect psychological differences largely indirectly, by influencing the effective environment of the developing child." This was a puzzling disclaimer since the entire study was repeatedly showing the weakness of the environment in development compared with genetic endowment and might be seen as a strained effort to assure the hardliners that their cherished environment was still important (if only to transmit genetic effects).

In pointing out that their heritability figure for intelligence of .70 was somewhat higher than the earlier studies, the paper saw an explanation in that those studies primarily involved adolescents, whereas the Minnesota twins were closer to middle-aged. Other research had shown that heritability of most traits Increases with age - that is twins grow more alike as they grow older (a surprising statistic in light of the increased opportunity for environmental factors to work their effects) -so that the Minnesota I.Q. finding was not really inconsistent with prior studies.

As always with such papers, the Minnesota report in Science naturally went into detail about the study's methodology and offered mean figures on the degree of separation and age at reunion, among others. Because of the informed-consent agreement, which promised the twins anonymity, the article provided no biographical information about individual twins, either anecdotal similarities or specifics about time of separation or age at reunion, or any information that might be used to identify a particular pair.

The core of the paper was a table that listed all of the traits examined with the percentages of correlation of the MZAs and the MSTs. The MZA correlation figures ranged from .96 for finger-ridge count to a .33 mean for social closeness. In other words, of the twenty-eight categories listed, including both physical and personality characteristics, every figure showed at least some degree of genetic influence. Most of the figures clustered around the more than merely significant 50 percent area.

In their conclusions Bouchard and his colleagues stated that the evidence indicated that parents might be able to increase the rate at which their children develop cognitive skills, but they will have "relatively little influence on the ultimate level attained." Later, more diplomatically, they said: "The remarkable similarity in MZA twins in social attitudes (for example, traditionalism and religiosity) does not show that parents cannot influence those traits but simply that this does not tend to happen in most families."

With that caveat Bouchard held out a less frightening alternative than powerful genes: ineffectual parents. If children do not turn out as we would wish, we would rather hear that the fault lies with the parents, whom we can improve, than with the genes about which we can do little. It is with asides like this that the Minnesota group revealed its awareness of the affront their findings would be to the cadres of psychologists who had based their therapies and problem-solving strategies on environmental assumptions this study was now demolishing.

In the paper's principal conclusion, however, that in every trait investigated genes prove to be an important source of variation, they sounded a strident note: "This fact need no longer be subject to debate; rather it's time instead to consider its implications."

The paper ruminated about an evolutionary explanation for the high degree of variation among humans, the apparent fact that newborn babies are already different from each other, before the environment has had a chance to work its influences. The paper cited one theory that says there is no point to these individual differences and considers them "evolutionary debris." Another believes them to have an adaptive function that has been selected for. Many Darwinians consider the small differences the Minnesotans were measuring, the variations that make humans more interesting than fruit flies, to be the engine that drives evolution. This is hard to digest in that it suggests that if you and your sister are very different, one of you may be launching a new direction for the entire species.

The Minnesota writers left it to the evolutionary theorists to make sense of the human-difference phenomenon but said that a species that was genetically uniform would have created a very different society from ours; whatever the origin of human variation, it "is now a salient and essential feature of the human condition." Not to mention the basis of every novel, play, poem, opera, and sitcom ever written.

Behind all writings on genetic influence over personality and behavior, there are inevitably political undercurrents, as there are with any theories that touch all humans. In scientific papers these political substrata usually push close to the surface in the broad generalizations at the end that often address implications. Saying that present-day society is a product of human variation might seem safe enough on the face of it, but the assertion is surely a red flag to someone who might see a hint that our social structures are, thanks to genes, inevitable. If this implication was found, it would be branded the status-quo justifying that evolutionists have been accused of since Darwin, sometimes with good reason. The paper's conclusion was remarkably simple: People are different, and they are different to a large degree because of genetic differences. While this would not seem to be a belligerent manifesto for revising political thought, to some it was just that and they marshaled their forces to combat it.

Born That Way: Genes, Behavior, Personality. Wright, p. 52-58.

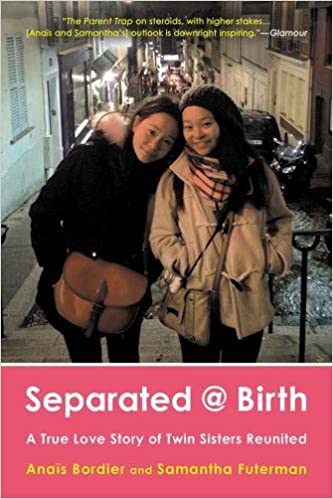

Twin Sisters Separated at Birth Reunite on 'GMA'

The thirty-five years of work in developmental psychology of Harvard's Jerome Kagan has made him a leader in his field. His main area of interest has been the inhibited and uninhibited child - primarily because this is an adult characteristic that is also observable in very young infants and can be monitored over years. His numerous writings on this and other subjects, his scientific dedication, and his cant-free style of communicating have all combined to make him one of the most honored and respected American psychologists.

Like most everyone of his generation, Kagan started out as a staunch environmentalist, a disciple of Skinner and Watson. When he decided to go into developmental psychology, it was not as an abstract quest for pure knowledge but was colored by strong altruistic ambitions. This was a period when all behavior was considered learned, including the behavior that produced social problems. If psychologists could unravel the precise mechanisms of learning and pinpoint the environmental causes for children developing as they do, educators and social scientists would be positioned to improve society greatly by averting the developmental mishaps that lead to poverty, ignorance, and crime.

Kagan's first research was in 1957 at Antioch College, when he was brought in on an existing developmental study of inhibited children who had already been assessed in the first months of life. For his initial assignment, Kagan was asked to conduct follow-up interviews with the study group, who were now young adults. Along with his colleagues, Kagan was surprised to find that the children who had been extremely fearful as infants remained so throughout adolescence and into adulthood.

He later recalled thinking how remarkable it was that the effects of the parents' rearing during the first months of life could have such an indelible effect. So imbued was he with the environmentalist creed, he, like his colleagues, never entertained the possibility of a genetic explanation. When I interviewed him in 1994, Kagan, looking back on this period, said his blinkered vision was especially remarkable since in a nearby Antioch laboratory a team investigating heart-rate variations had found a connection between fearfulness and heart rate. While this finding strongly suggested a biological basis for fearfulness and a link between physiology and psychology, the researchers took the idea no further with a kind of "we don't want to go there" reticence. The concept of fearful children having been born that way was totally alien to mainstream psychology in the 1950s. No one was born any "way"; we were all at birth tabulae rasae, innocent, raw, and ready for the world to do its worst. Such was the faith in the environment's omnipotence in the heyday of behaviorism.

For Kagan this faith began to weaken in the early seventies, when he spent a year in Guatemala observing infants in a remote mountain village. The village children were of particular interest because of an unusually deprived first year of life that sprang from the Indians' tradition. Local custom had the mothers isolating their children inside cramped dark huts for the first year, never allowing them outside, never playing with them, and almost never speaking to them. As a result, the children at the ages of one and two were observed to be unusually passive, quiet, and unresponsive. To Kagan, some appeared borderline retarded.

Settling to work, Kagan and his colleagues set up a controlled study in which the village kids were measured on a number of cognitive functions. Those results were then compared with a Guatemalan group raised in a more normal fashion near a city and with a group of middle-class American children. The three groups might roughly be termed understimulated, normally stimulated, and overstimulated.

The results showed that while the deprived village children measured lower in all tests in the first years, they tended to catch up as they grew older and their rearing setting became more similar to those of childhoods everywhere - outdoor play, interaction with parents, with other children, and so on. By eleven and twelve the Guatemalan children could be considered normally developed. This transformation was heartening to environmentalists like Kagan and to socially concerned individuals who placed hopes in intervention programs like Head Start which help underperforming children catch up with their age groups. Good behaviorist soldier that he was, Kagan wrote in an early paper on this study, "The data prove the potency of the environment." Without hesitating he credited the good environment with remedying the effects of the bad.

But the data, he came to realize, could be seen in two ways. With the Guatemalan village children, there had been no intervention, no remedial program; they had merely been delivered from the negative environment of their first year, the dark hut. Something else seemed to be causing their improvement, and future evidence indicated it was their own normal development, in all likelihood their own genetic makeup triumphing over an adverse environment. Rather than the normal "outdoor" environment curing the negative effects of the grim first year, it may have merely allowed the child's personality to unfold as its genome, or as "nature," intended. While Kagan did not express it in those terms, he would later say something very close to the same thing, but in a turned-around way: "My belief in the power of early experience [in children's development] was shaken."

Shaken, perhaps, but Kagan, like the rest of the psychological profession, continued to believe in the environment as the most important molder of personality. His epiphany came fifteen years later, when he was working in Boston on a longitudinal study of infants, observing them from seven to twenty-nine months, with the aim of assessing the effectiveness of day care. The group was made up of fifty-three Chinese-American infants and sixty-three Caucasian children. Part of the entire group had from the age of four months attended an experimental day-care center set up for the study, part had attended other day-care centers, and part had been raised at home.

In the course of the experiment, Kagan noticed something unanticipated. The Chinese children, little more than babies, whether attending day-care or raised at home, were consistently more fearful and inhibited than the Caucasians. The differences were obvious. The Chinese children stayed close to their mothers and were quiet and generally apprehensive, while the Caucasians were talkative, active, and "prone to laughter." These characteristics were confirmed by the mothers as typical of their children's behavior at home as well. In addition, the researchers discovered that the Chinese tots had less variable heart rates than the Caucasians. Kagan could not avoid the clear evidence of an innate difference between the two groups of infants.

It is ironic that this scientist's conversion to a biological-genetic point of view came along the lines of racial differences. Kagan was a political liberal who only three years earlier had been one of the most vociferous critics of Arthur Jensen's theories on the heritability of I.Q., theories that he and most everyone else denounced as racist. Now he was publishing his observations of fundamental personality differences between racial groups. When we conversed in his Harvard office many years later, I asked Kagan if there had been an uproar similar to the one Jensen provoked.

He smiled. "We got no flak on the Chinese paper. All the reports of the book were about our day-care findings. Everyone ignored the fact that the Chinese children were different. I think it was because they were Asians, and Asians do well. If they had been black, we probably would have gotten flak."

Asked if it was dismaying for him, an unwavering liberal, to observe inherent racial differences, Kagan snapped, "Nature doesn't care what we want." More reflectively, he added, "I wasn't so much dismayed at my observations of the Chinese kids...I was a little bit saddened to see the power of biology."

His major conclusion was stated in a 1988 paper in Science: "We suggest, albeit speculatively, that most of the children we call inhibited belong to a qualitatively distinct category of infants who were born with a lower threshold for limbic-hypothalamic arousal to unexpected changes in the environment or novel events that cannot be assimilated easily."

It is revealing that in a sentence that is basically saying "kids are born that way," Kagan, who had thrown himself into a self-education program of brain biochemistry, manages to avoid the word genes yet does find a way to work in the word environment. In the article's abstract he speaks of "the inherited variation in the threshold of arousal in selected limbic sites." But still, not a gene in sight. He appears to be worried about the limbic-hypothalamic arousal of the environmentalists down the hall. Or the word gene may have been forbidden at Harvard at the time. A more likely explanation is that Kagan, as a new convert to biology of behavior, could not switch so quickly to the terminology of the infidels.

In his study of brain chemistry, Kagan grew convinced of the major effect on the traits he was examining of the liquid mix of neurotransmitters, hormones, and opioids that surround the operating parts of the brain. This mixture, which he refers to as "the chemical broth," is made up of 150 chemicals in combinations that vary within individuals. While he believed there might be hundreds of possible combinations, his research had found two: ones that raise the threshold of excitability leading to inhibited children and ones that lower it to produce uninhibited children. This was a remarkable area of investigation for a behavioral psychologist who for years had believed in the sovereignty of the environment and had fought off any notion of biological or genetic influence on behavior. Kagan was, so to speak, in the soup.

Today, Kagan is hard on himself about his earlier unquestioning allegiance to the day's psychological dogma. "I wince at my credulity when I told several hundred guileless undergraduates in 1954 that rejection by the mother could produce an autistic child." He also speaks of his regret at wasting so many years ignoring the genetic contribution to behavior; he forthrightly admits that the omission confounded all his research. Although, like Kagan, few in his profession still believe in the environmental determinism that dominated psychology in those years, few have Kagan's honesty in admitting the scope of the mistake.

Speaking about his changed perspective, Kagan said, "I was the classic politically liberal environmentalist who believed that genes had minimal effect on behavior. Now, I am quite a different person. My data has pushed me toward granting much more power to genetic mechanisms than I would have believed twenty years ago. I arrived here honestly, without prejudice, which is a good way." In another interview he said, "For the first twenty years of my career, I wrote essays critical of the role of biology and celebrating the role of the environment. I am now working in the opposite camp because I was dragged there by my data."

In his 1994 book with a subtly significant title, The Nature of the Child, Kagan speculates about ways in which the genetic differences in brain chemistry of inhibited children might have evolved into the species. Noting that the thin body builds (ectomorphs) and blue eyes that are more typical of inhibited children predominate in northern Europe, Kagan puts forward the possibility that when humans migrated from Africa and arrived in northern Europe some forty thousand years ago, evolution might have favored mutations that would be beneficial in the more challenging cold environments. His experiments had shown that inhibited behavior is linked to a greater efficiency in the sympathetic nervous system and an increased production of a major neurotransmitter, norepinephrine. Kagan wrote: "Because the metabolic steps in the manufacture of norepinephrine are mediated by several different enzymes, some of which are controlled by one or a few genes, it is possible that such a change in DNA occurred."

Not only was Kagan tracing a human behavioral facet, inhibition, to specific genes, he was also speculating about evolution's role in bestowing those genes upon certain groups of humans. Whatever weight the theory might have, for the field of behavioral genetics it was exciting to have a mind of Kagan's caliber and a psychologist of his experience to be thinking at last in genetic-evolutionary terms.

Born That Way: Genes, Behavior, Personality. Wright, p. 89-94.

Five Counterintuitive Insights from Behavioural Genetics https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/review-blueprint-how-dna-makes-us-who-we-are-by-robert-plomin-why-nature-always-trumps-nurture-0cp7r2dsd … From @mattwridley's review of @RobertPlomin's new book Blueprint: How DNA Makes Us Who We Are

2 Full-Blooded Brothers, But Disposition And Personality Wise They Couldn't Be More Different!

What Makes One Child In A Family Different From Another?

Their Genes (The 50% They Inherited From Their Father And The 50% They

Inherited From Their Mother Which Differ From The 50% And 50% That

Their Siblings Inherited) And Their Non-Shared Environment, Which

Includes All Of The Environmental Effects That Their Siblings Didn't

Experience Or Only Experienced To A Lesser Extent. So, Let's Take My

Sister Katy And I, For Example. We Have The Same Parents, But We Inherited Different Genes From Each Of Our Parents And These

Different Genes Then Led To Us Being Treated Differently By Our Parents,

Which Then Amplified These Differences In Our Genetic Makeup (This

Different Treatment By Parents Accounts For Some Of The Non-Shared

Environment That I Mentioned Above). So, To Begin With, I Was Born A

Male And My Father Favored Males. Secondly, My Genetically

Inherited Facial Features, Body Type, Personality And Temperament As An

Infant, Toddler, Adolescent, Etc. Were More Appealing To My Parents

And Siblings Than Were Katy's, So This Further Lead To Them Treating ME

Differently (Them Favoring ME). Etc., Etc., Etc. There Were Many Other

Factors At Play, But The Bottom Line Is That Because Of My Different

Genetic Makeup At Conception More Time, Money, Effort, Energy, Etc. Was

Invested In ME, Especially By My Father*, Than Was Invested In Katy. And

This Ultimately Led To The Differences In Our Personality, Attitude**,

Mentality, Beliefs, Lifestyle, Penchants, Preferences, Propensities,

Choice Of Friends, Mates (Eventual Spouses), Career, Hobbies, Etc.,

Etc., Etc.**Why Do I Have Such An Elitist, Egotistical, Pretentious Outlook And Attitude? Probably Because Of My Genes That Influence Personality, But Mostly Because Of My Experiences In Life, Experiences Which Included Dominating All Of My Peers In Sports Growing Up, Getting Attention And Praise From All Types Of People For Being Such A Good Athlete, Good Student With Good Looks, A Good Disposition And Personality, Etc. And, Last But Not Least Being, Exposed To The Good Life By My Father, i.e. Upper Class Living! GET IT (GETTIN IT PIMP).

UNCLE TOM'S CABIN

I WAS ADOPTED!

Not At All, Chris Elliot, Not At All (It's Small, Chris! It's A Small Whirl!)

Mind Reading Or Telepathy Or Clairvoyance Or ESP Or Any Of That Other

Shit Doesn't Exist. What Does Exist Is Theory Of Mind Or The Ability To

Infer (Guess) What Someone Else Is Thinking Based On Your Own Thoughts

And Feelings Or The Thoughts And Feelings You've Seen Other People

Experience. So, For Instance, I CAN WRITE STUFF ON THE INTERNET AND THEN

ASSUME HOW MY VIEWERS ARE INTERPRETING OR REACTING TO THE THE STUFF I'M

WRITING ON THE INTERNET WITHOUT EVER SEEING MY VIEWERS OR HEARING MY VIEWERS BASED

ON HOW I'D INTERPRET AND REACT TO THIS STUFF OR BASED ON HOW I'VE SEEN

OTHER PEOPLE INTERPRET AND REACT TO THIS STUFF. In Other Words, Theory

Of Mind Allows You To Put Yourself Into Someone Else's Mind And

Speculate As To How They'd Think And Feel About Something Or How They'd

Respond To Something. With Respect To Your Twin Sister, You May Think

That You Can Tell What She's Thinking Without Her Speaking Or Read Her

Mind, But In Actuality You're Really Just Using Your Theory Of Mind To

Infer (Guess) What She's Thinking. And The Fact That Both Of You Share

100% Of Your Genes Only Makes The Likelihood Of You Accurately

Inferring What She's Thinking Even Greater, Since The Genes That

Created Her Brain Are The Same Genes That Created Your Brain (Brains

That Are Wired The Same Tend To Have Minds That Are The Same, Which Tend

To Have Thoughts That Are The Same).

http://www.unz.com/isteve/pinker-on-genealogy/

The first is the simple fact that blood relatives are likely to share genes. To the extent that minds are shaped by genomes, relatives are likely to be of like minds. Close relatives, whether raised together or apart, have been found to be correlated in intelligence, personality, tastes, and vices...

The first is the simple fact that blood relatives are likely to share genes. To the extent that minds are shaped by genomes, relatives are likely to be of like minds. Close relatives, whether raised together or apart, have been found to be correlated in intelligence, personality, tastes, and vices...

2 Full-Blooded Brothers Who Share 50% Of Their Genetic Makeup, But Who Held Completely Different Worldviews!

When studies were run to examine this idea, it was found that the nonshared environment played a much bigger role than the shared one. In fact, the shared environment, the one previously assumed to be the only environment, turned out to have a negligible effect on personality development. Brothers and sisters were rarely much alike, and, to the degree that they were, the similarities were found to be genetic, not environmental.

The other major new conceptual shift was that the fundamental environment children start with may not be free of genetic influence. Previously it was thought that if a child grew up in a family of animal lovers, surrounded by pets, that milieu was considered environment, plain and simple. As such, it would be cited as the explanation for the child's fondness for animals. With the broadening genetic perspective, however, the houseful of pets might be seen as a manifestation, at least in part, of the parents' genes, elements in the parents' fundamental nature that distinguished them from others. And if the parents' love of animals had a genetic basis, these genes could well be shared to a degree by the offspring. Pets and genes were hopelessly mixed. And while the traditional psychological view had been that the pets were a molding environmental influence, it now turned out that the pets and the child's love of pets might both be expressions of genes shared by parent and child.

Ethologists had long known that many organisms go a long way toward creating their own environment - everything from earthworms producing the soil they move through to the beavers living in lakes they themselves created. Their environments were seen by some ethologists as functions of their genetic makeup - or to use Richard Dawkins's phrase, such self-made environments were manifestations of "the extended phenotype." According to this concept, the line between an organism and its environment grows indistinct. To Dawkins, the beavers' dams were extended manifestations of their genes. Carried further, this idea would suggest that an individual's hobby, career, and marriage might be seen as extensions of his or her genotype. They would be colored and shaped by the environment, to be sure, as hair color and skin texture are, but manifestations of genes all the same.

An example of molding one's environment could even be seen in a child of a few months, one young enough for the environment to have little opportunity to twist and form. Except for those that cling to the blank-slate notion, most would agree that an infant, in the first months after birth, is pretty much a raw genetic package. If genes produced a fussy, irritable baby boy, he would confront very different parents than his well-behaved brother and sisters. He would have made his environment different than theirs. In school, the hyperactive, inattentive child with find himself facing a hectoring, hostile teacher who is nice as a pie to the child's model classmates. Carrying this mechanism to an extreme, the most problematic, troublemaking child may, as he grows, find himself in a special school, a reformatory, or a juvenile prison, in which case he will have succeeded in changing his environment totally.

...Genes and environment were now recognized to be deeply entwined. Each child was seen as having a unique genetic makeup and a unique environment as well, a portion of which was determined by the child's genes. (Born That Way)

NOT AT ALL (They Don't Know)

Look That Way! Those Persians Sisters I Was Tellin' Y'all 'Bout!

On the day I began writing this book, Laleh and Ladan Bijani were buried in Iran, in separate graves: apart in death as they had never been in life. Laleh and Ladan were conjoined identical twins, twenty-nine years old, born attached at the head. They died during the surgery that separated them.

In their twenty-nine years of enforced togetherness, Laleh and Ladan had accompanied more than most Iranian women of their generation: both had graduated from law school. They were able to sit and to walk because they were joined side by side, facing in the same direction. But the only way each twin could see the other's face was by looking into a mirror.

Laleh and Ladan went into the surgery knowing the risks; physicians had told them that they had only a 50-50 chance of surviving it. They were willing to take that risk for the chance of living separate lives. "We are two completely separate individuals who are stuck to each other," Ladan explained to reporters before the surgery. "We have different world views, we have different lifestyles, we think very differently about issues." Laleh wanted to move to Tehran and become a journalist, while Laden planned to remain in their hometown of Shiraz and practice law. Ladan was the more outspoken of the two, described by a close acquaintance as "very friendly, she always liked to joke."

The conflict in career goals was one reason they gave for undergoing the surgery. Another was their desire to see each other face-to-face without a mirror. There may have been other reasons that they didn't want to admit to reporters - their desire to marry, perhaps, and to have children. Having to go everywhere with one's sister can be a bit awkward at times. Researchers have found (and Laleh and Ladan might have discovered on their own) that someone who falls in love with one identical twin may not even like the other one.

Though identical twinning is nature's way of making a clone, twins are separate and unique individuals, to themselves and to the people who know them. Laleh and Ladan had identical genes and identical environments - they went everywhere together, they had no choice - but their personalities, opinions, and goals in life were different. That individuality was what they died for.

Most identical twins are not born fastened together, of course, and most conjoined twins do not seek surgical separation in adulthood. But identical twins invariably differ in personality. Why they differ is a mystery that science has so far been unable to solve and that twins themselves are puzzled by.

"Why am I me?" That question was put to Freeman Dyson, professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, by his eight-year-old grandson George. I don't know what he said to George, but Dyson later told an adult audience that the question "summarizes the conundrum of personal existence in an impersonal universe." Um, I suppose so. But the real question had a more specific meaning for George, because he is an identical twin. According to his grandfather, George knows the difference between identical (monozygotic) and fraternal (dizygotic) twins, and he knows that he and his twin brother Donald are genetically identical. He is also aware, according to his grandfather, that he and his twin "have the same environment and upbringing" - they are growing up in the same home with the same parents. When George asked "Why am I me?" he was asking, his grandfather gathered, "how it happens that two people with identical genes and identical nurture are nevertheless different." If their nature is the same and their nurture is the same, how come the have different personalities?

...

http://articles.latimes.com/1998/may/09/news/mn-47944

http://lasvegassun.com/news/1996/nov/18/no-love-lost-between-twins/

Those Korean Sisters I Was Tellin' Y'all 'Bout. They Share The Same Genes, But Have Vastly Different Personalities. Why? because Of Non-Shared Environment, Which Includes How They Were Treated By Their Parents, How They Were Treated By Teachers And Other People Of Authority, How They Were Treated By Peers, And The Type Of Peers They Associated With (Which May Have Been Different). All Of These Non-Shared Environmental Factors (Differences In Environment Between Them) As Well As Slight Genetic And Biological Differences Led To Their Different Life Outcomes.

"YOU NASTY TWIN! I DON'T CARE!" - BIG PUNISHER

McKinney, TX.

The difficulties involved in testing this theory are illustrated by a true story about a pair of identical twins. Conrad and Perry McKinney, age fifty-six, were featured in an article in the Boston Globe titled "Two Lives, Two Paths." Born and reared in New Hampshire, the twins did everything together in their early years. They attended the same schools, sat in the same classrooms. Academically they were average students, but they were troublemakers. Eventually their teachers got fed up with their shenanigans and the twins were separated: Perry was held back in fifth grade, Conrad was promoted to sixth. That, according to the Globe reporter, was where their paths diverged. Conrad went on to graduate from high school; Perry dropped out in eleventh grade. Today, Conrad is a successful businessman - as it happens, he runs a private detective agency. Perry...well, Perry is a homeless alcoholic "who sleeps amid trash under a bridge," by the Piscataqua River in New Hampshire.

This story shows, first of all, why ethical considerations make it impossible to test my theory by doing an experiment. We cannot tinker with the lives and futures of human beings. Testing my theory will therefore have to rely on "natural" experiments, provided by the world. The cruel experiment the world performed on Conrad and Perry produced results that were consistent with my theory. The theory predicts that if you change the way the community sees a child, and the change is substantial and persistent, the result will be a change in the child's personality. When a child is made to repeat a grade in school, it's a public event that changes the way the community sees him. Thereafter, when the child looks into his classmates' minds to find out what they think of him, he reads things like "dummy" and "loser."

But natural experiments tend to lack scientific rigor. When the decision was made to hold one twin back, did the teachers flip a coin and it came up Perry? Unlikely. More likely, they chose Perry because he was already doing a little less well in his schoolwork than Conrad, or acting a little more troublesome. It's even possible that Perry was already showing early signs of a mental illness that would worsen over the years.

Though identical twins are genetically identical (or nearly so), they have slightly different brains due to development noise or to minor injuries or infections. These little neurophysiological differences can result in differences in behavior, which means that if we find a behavioral difference between identical twins, it's usually impossible to tell whether it's due to the twins' experiences or to a preexisting difference in their brains. If people treat them differently and they behave differently, is the difference in how they're treated a cause or an effect of the difference in behavior? Even longitudinal studies can't answer this question. Researchers may find that differential treatment by teachers or peers at Time 1 is correlated with a difference in the twins' behavior at time 2. But the teachers or peers might be reacting to a difference in behavior that already existed at time, though it might not yet have been apparent to the researchers. The fact that some behavioral problems and mental illnesses show up in a mild form in the early years and worsen as time goes on doesn't prove that the worsening is due to the child's experiences: neurophysiology can work that way too.

Another problem in interpreting the story of Conrad and Perry is that being left back in school affects many aspects of a child's life, not just one. The status system, which keeps its owners informed about what other others think of him, might not have been the only perpetrator involved in Perry's long, slow slide: the socialization system could also have played a role. Left-back kids, though they're bigger than most of their classmates and hence rank high in the pecking order, tend to be poorly accepted. Kids who are rejected by their peers often get together and form groups of their own - in many cases, antisocial groups. The Globe reporter mentioned that after Perry was left back he "began to accumulate a circle of friends who were rowdier and more risk-taking" than Conrad's friends. This means that socialization by a delinquent peer group could be one of the reasons why Perry ended up the way he did. As it happened, the poor guy didn't have any luck in relationships, either. His wife died suddenly at the age of twenty-nine from an aneurysm. So all three systems may have conspired to put Perry under the bridge.

PERRY YALL.

Hey, How Can Siblings That Were Conceived By The Same Parents And Raised In The Same Home (Same Household) Be Nearly Polar Opposites In Adulthood? GENES. The GENES They RANDOMLY Inherited From The Parents That They Share. Take For Instance My Older Brothers And I. Although We Share The Same Parents And Thus 50% Of The Same Genes (Which We Inherited From Our Parents) They And I Differ In A Number Of Ways, Particularly With Respect To Our Worldview, Lifestyle, Interests, Peers, And Mates*. For Instance, None Of Them, Except For Richie (But Too A Much Lesser Degree), Are As Academically And Scientifically Inclined As I, Nor Are Any Of Them Atheists Who Are Ardent Adherents Of Evolutionary Theory And Adamantly Believe In The Reality Of Racial Differences (So Adamant About This Belief That I'm Particular About The Racial And Genetic Makeup Of Mates And Feel Hawaii Should Be Repopulated By A Racially Homogenous Polynesian People; i.e. Full-Blooded Hawaiians). Now How Did These Differences Come About? TO BE CONTINUED...

*I LIKE DARK-SKINNED GIRLS WITH THICK, COARSE HAIR WHO LOOK POLYNESIAN, INCLUDING BLACK GIRLS WHO FIT THIS DESCRIPTION. ALL OF MY BROTHERS' GIRLFRIENDS AND WIVES HAVE LOOKED NOTHING LIKE THIS (THEY'VE EITHER BEEN WHITE, HISPANIC, OR ASIAN WITH LIGHT SKIN, STRAIGHT HAIR, AND EUROPEAN OR ASIAN FACIAL FEATURES). WHY HAVE THEY LOOKED THIS WAY? I THINK FOR GENETIC REASONS. BY THE WAY, I KNOW FOR A FACT, THAT A COUPLE OF MY BROTHERS ARE REPULSED BY BLACK PHYSICAL/FACIAL FEATURES. THEY DON'T FIND NIGGERS ATTRACTIVE AT ALL. NOT AT ALL PIMP!

...

http://articles.latimes.com/1998/may/09/news/mn-47944

http://lasvegassun.com/news/1996/nov/18/no-love-lost-between-twins/

Those Korean Sisters I Was Tellin' Y'all 'Bout. They Share The Same Genes, But Have Vastly Different Personalities. Why? because Of Non-Shared Environment, Which Includes How They Were Treated By Their Parents, How They Were Treated By Teachers And Other People Of Authority, How They Were Treated By Peers, And The Type Of Peers They Associated With (Which May Have Been Different). All Of These Non-Shared Environmental Factors (Differences In Environment Between Them) As Well As Slight Genetic And Biological Differences Led To Their Different Life Outcomes.

"YOU NASTY TWIN! I DON'T CARE!" - BIG PUNISHER

McKinney, TX.

The difficulties involved in testing this theory are illustrated by a true story about a pair of identical twins. Conrad and Perry McKinney, age fifty-six, were featured in an article in the Boston Globe titled "Two Lives, Two Paths." Born and reared in New Hampshire, the twins did everything together in their early years. They attended the same schools, sat in the same classrooms. Academically they were average students, but they were troublemakers. Eventually their teachers got fed up with their shenanigans and the twins were separated: Perry was held back in fifth grade, Conrad was promoted to sixth. That, according to the Globe reporter, was where their paths diverged. Conrad went on to graduate from high school; Perry dropped out in eleventh grade. Today, Conrad is a successful businessman - as it happens, he runs a private detective agency. Perry...well, Perry is a homeless alcoholic "who sleeps amid trash under a bridge," by the Piscataqua River in New Hampshire.

This story shows, first of all, why ethical considerations make it impossible to test my theory by doing an experiment. We cannot tinker with the lives and futures of human beings. Testing my theory will therefore have to rely on "natural" experiments, provided by the world. The cruel experiment the world performed on Conrad and Perry produced results that were consistent with my theory. The theory predicts that if you change the way the community sees a child, and the change is substantial and persistent, the result will be a change in the child's personality. When a child is made to repeat a grade in school, it's a public event that changes the way the community sees him. Thereafter, when the child looks into his classmates' minds to find out what they think of him, he reads things like "dummy" and "loser."

But natural experiments tend to lack scientific rigor. When the decision was made to hold one twin back, did the teachers flip a coin and it came up Perry? Unlikely. More likely, they chose Perry because he was already doing a little less well in his schoolwork than Conrad, or acting a little more troublesome. It's even possible that Perry was already showing early signs of a mental illness that would worsen over the years.

Though identical twins are genetically identical (or nearly so), they have slightly different brains due to development noise or to minor injuries or infections. These little neurophysiological differences can result in differences in behavior, which means that if we find a behavioral difference between identical twins, it's usually impossible to tell whether it's due to the twins' experiences or to a preexisting difference in their brains. If people treat them differently and they behave differently, is the difference in how they're treated a cause or an effect of the difference in behavior? Even longitudinal studies can't answer this question. Researchers may find that differential treatment by teachers or peers at Time 1 is correlated with a difference in the twins' behavior at time 2. But the teachers or peers might be reacting to a difference in behavior that already existed at time, though it might not yet have been apparent to the researchers. The fact that some behavioral problems and mental illnesses show up in a mild form in the early years and worsen as time goes on doesn't prove that the worsening is due to the child's experiences: neurophysiology can work that way too.

Another problem in interpreting the story of Conrad and Perry is that being left back in school affects many aspects of a child's life, not just one. The status system, which keeps its owners informed about what other others think of him, might not have been the only perpetrator involved in Perry's long, slow slide: the socialization system could also have played a role. Left-back kids, though they're bigger than most of their classmates and hence rank high in the pecking order, tend to be poorly accepted. Kids who are rejected by their peers often get together and form groups of their own - in many cases, antisocial groups. The Globe reporter mentioned that after Perry was left back he "began to accumulate a circle of friends who were rowdier and more risk-taking" than Conrad's friends. This means that socialization by a delinquent peer group could be one of the reasons why Perry ended up the way he did. As it happened, the poor guy didn't have any luck in relationships, either. His wife died suddenly at the age of twenty-nine from an aneurysm. So all three systems may have conspired to put Perry under the bridge.

PERRY YALL.

Hey, How Can Siblings That Were Conceived By The Same Parents And Raised In The Same Home (Same Household) Be Nearly Polar Opposites In Adulthood? GENES. The GENES They RANDOMLY Inherited From The Parents That They Share. Take For Instance My Older Brothers And I. Although We Share The Same Parents And Thus 50% Of The Same Genes (Which We Inherited From Our Parents) They And I Differ In A Number Of Ways, Particularly With Respect To Our Worldview, Lifestyle, Interests, Peers, And Mates*. For Instance, None Of Them, Except For Richie (But Too A Much Lesser Degree), Are As Academically And Scientifically Inclined As I, Nor Are Any Of Them Atheists Who Are Ardent Adherents Of Evolutionary Theory And Adamantly Believe In The Reality Of Racial Differences (So Adamant About This Belief That I'm Particular About The Racial And Genetic Makeup Of Mates And Feel Hawaii Should Be Repopulated By A Racially Homogenous Polynesian People; i.e. Full-Blooded Hawaiians). Now How Did These Differences Come About? TO BE CONTINUED...

*I LIKE DARK-SKINNED GIRLS WITH THICK, COARSE HAIR WHO LOOK POLYNESIAN, INCLUDING BLACK GIRLS WHO FIT THIS DESCRIPTION. ALL OF MY BROTHERS' GIRLFRIENDS AND WIVES HAVE LOOKED NOTHING LIKE THIS (THEY'VE EITHER BEEN WHITE, HISPANIC, OR ASIAN WITH LIGHT SKIN, STRAIGHT HAIR, AND EUROPEAN OR ASIAN FACIAL FEATURES). WHY HAVE THEY LOOKED THIS WAY? I THINK FOR GENETIC REASONS. BY THE WAY, I KNOW FOR A FACT, THAT A COUPLE OF MY BROTHERS ARE REPULSED BY BLACK PHYSICAL/FACIAL FEATURES. THEY DON'T FIND NIGGERS ATTRACTIVE AT ALL. NOT AT ALL PIMP!

Posts From This Book Coming Soon http://www.amazon.com/No-Two-Alike-Nature-Individuality/dp/0393329712